Singing the Mauritanian Blues

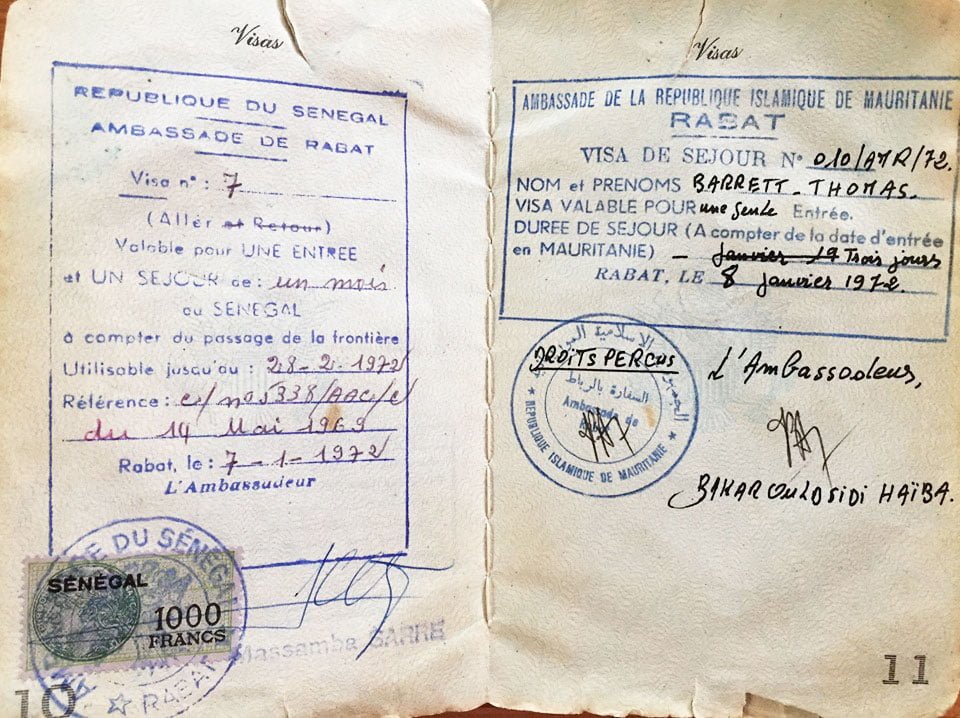

The dusty little town of Bir Moghrein, where I was dropped off in early February, 1972, was not the end of the world, but it was pretty damn close. It is located in northern Mauritania, a very large but little known former French colony, one of the last remaining countries where slavery is illegal, but still widely practiced. A long conflict with Polisario guerrillas (the Sahrawi national liberation movement) which began in early 1973 still continues. Happily, I missed the violence by a year.

There were less than 1,000 people living in Bir Moghrein when I arrived and there was nothing to do except endure the excruciating boredom until I could hop on the back of a truck headed in the general direction of Senegal on the other end of the western Sahara Desert. In the 47 years since I travelled through Mauritania I have never met anyone who has ever been there and very, very few people who have ever even heard of the country.

After saying goodbye to the driver who took me to Bir Moghrein I decided to go truck shopping and explore the virtual ghost town, but quickly learned the only truck was the one I rode in on. There was absolutely nothing to do there but wait. And wait. And wait. Any truck headed this way and continuing southbound would likely be coming from Algeria. There might also be some locals with trucks bringing supplies to southern Mauritania. There was a massive iron ore mining operation about 600 km to the south near a small city called Zouerat. A little further south was the smaller city of Atar. Those communities would definitely need supplies and the only other option would be a truck coming north from Nouakchott, Mauritania’s capital, more than 1,000 km away.

I was hungry and went searching for food. I could not find a single restaurant and there was only one very poorly supplied general store. I didn’t have any cooking equipment and I could find only one thing on the dusty shelves that I could consume – large cans of cold peas. It did not look very appetizing, but I figured it would do until the next day, so I pulled out my trusty Swiss Army Knife and used the little can opener to pry open the top, bent it back and gobbled down the near tasteless peas using the tiny spoon on the knife. It was pretty wretched but it would keep me going until the cavalry arrived. I set up my tent, crawled inside and went to bed hoping things would be better the next day.

No luck. Another slow day followed. There wasn’t much to do in Bir Moghrein, apart from walking around the place and as the day got hotter the swarms of flies became more and more intrusive and annoying. I tried walking down the rough dirt road to the south out of curiosity, but the flies just got worse and worse, driving me back to my tent to escape them. I concluded that the fly must be Mauritania’s national bird.

The next day there were still no signs of any trucks heading south. It was unbelievably depressing. I didn’t have a book to read and there was no chance of buying one in English. There was nothing else to do but wait, and then have a few more cans of cold peas. Ugh. This was definitely the downside of budget travel, but for me it was worth the trouble, despite everything. It was the price you had to pay for a real adventure. A couple of American backpackers showed up that day, but the truck that dropped them off was heading back to Layounne, where I started. They were also headed south, so at least I was no longer the only foreign traveller in town. The following day was exactly the same. No trucks, nothing to do, more cans of cold peas. Get me out of here.

Just when I was beginning to contemplate spending the rest of my life in that godforsaken town, a truck arrived the next day, not just heading south, but going all the way to Nouakchott, 1,120 km away and just 200 km north of the Senegal River, the gateway to black Africa. I was ecstatic. The two Americans and I asked the driver how much it would cost to ride on top of the cargo in the open back of the truck. Riding up front was not possible because the driver had a partner sitting there. He asked for the equivalent of $8 US (2,000 West African francs) and I quickly said yes. It was going to be a long two-day ride and it was a fair price. He could have asked for more and I would have accepted. I didn’t want to see another can of cold peas ever again. To my bewilderment the Americans began bargaining with him, offering $6, but the driver would not budge. It was a genuine Mauritanian standoff. Finally, the Americans walked away and never did get on the truck. I hoped they enjoyed the local cuisine and recreational opportunities in Bir Moghrein for a few more days.

I hopped aboard the back of the truck and found a place, riding on top of what felt like steel bars. It was a very uncomfortable journey, bouncing up and down on the hard metal as we bumped our way down the rough dirt track for hour after hour. I could tell I would have a bruised butt by the time this ride was over, but six months of hard travel had toughened me up and trimmed me down. I am 5’10” and-a-half and my usual weight back then was about 150 to 155 pounds. At the end of my African journey I weighed in at a rail-thin, but hard as nails, 129 pounds. I couldn’t get down to that weight again now without the assistance of a concentration camp.

As the ride continued it grew insufferably hot and I could see that even the many Africans riding in the back were beginning to suffer. The ride was so rough and the temperature was so high that a couple of them threw up over the side of the truck. It scared me to think that I was able to handle these conditions better than some of the locals. Maybe I had been travelling rough for a little too long. We rode on until night fell, at least making the temperature easier to handle.

Suddenly the truck slowed down and came to a stop in what appeared to be an empty space. I wondered what was going on. I heard the vague murmuring of voices in the distance and they slowly became clearer as they neared the truck. One of the voices sounded horrifyingly familiar. It couldn’t be. Not again. Please no. Dominique climbed on board and spotted me. “Ha, ha, we meet again my friend!” he announced. And then for dramatic emphasis. “I’m still on my way!”

The prospect of sitting in the back of a truck with Dominique for the next 24 hours or so was very unappealing, but I had no choice. I didn’t even ask him how on earth he ended up in the middle of the desert with literally nothing of any kind in the vicinity. Or how come I didn’t see him in Bir Moghrein. Was there another track that skipped Bir Moghrein? Did he get dumped on the side of the road because he was too annoying to transport any further? He was on his own now because he certainly wasn’t with me. I had to admire his spirit, but I wasn’t sure if he was good luck or bad ‘juju’ as the Africans called it. When I considered his behavior and the actions of the two Americans, who were surely still swatting flies and munching cold peas back in Bir Moghrein, I wondered if you had to be at least a little bit crazy to make this journey.

After many hours we stopped in Zouerate, the iron ore mining centre, and grabbed a bite to eat. I don’t remember what we ate, but it was delicious after days of cold peas. Later we drove on to an outpost near Atar and the passengers slept on top of the cargo, as best we could. I stuffed my wallet and passport in my unpickably tight, front-pants pocket and had a good snooze. We headed on in the morning, with a few less passengers, and bounced along all day under the searing rays of the sun. The Atar area was the only place in the Sahara that I saw some genuinely beautiful sand dunes. As evening approached we reached the outskirts of the capital city, Nouakchott. There was an impressive, well-paved road at a turnoff leading into the city, but I asked to be let off, so I could hitchhike on the road south to Rosso, the border crossing beside the Senegal River. I did not say goodbye to Dominique and never saw him again, but heard through the backpacker’s grapevine that he made it to the Senegalese capital, Dakar. He was an unforgettable rascal and character, like the notorious Cheap John, whom I was soon to meet.

I stuck out my thumb and just as it was getting dark a local

young man on a motorbike stopped to offer me a lift. It was massively

uncomfortable riding on the back of the bike with my backpack on and my fingers

desperately gripping the back of the bike seat but I was hungry to reach

Senegal at last. He dropped me off about 150 km from the border. Finally, I got

a ride to Rosso, found some space, put up my tent and slept blissfully.

In the morning I got up and walked through town to the shores of the Senegal

River. It was now nearly three weeks since I left Marrekech, hoping I could

cross the desert. I got my exit stamp from a Mauritanian official, boarded an

exotic looking pirogue canoe rowed by two locals using paddles in the shape of

lion claws. I felt as though I was riding through the pages of the National Geographic. Everything looked

totally different from Morocco, Mauritania and the Spanish Sahara. It was lush

and wild and intoxicating. The Africa of my dreams.

I stepped off the pirogue, walked into the immigration shack and was promptly informed that I wasn’t going to be admitted to Senegal, despite my visa, without a major haircut. The French speaking official repeated in broken English “not proper,” and “not correct,” pointing at my unruly mop of hair.

I had no choice but to cross the river back to Rosso in Mauritania. I did, and then went searching for a barber shop of any kind. I found one and the barber said for $1 he would lend me a pair of scissors and the use of his big mirror. I don’t think he wanted any part of cutting my hair. Minutes later, a vast amount of that hair was lying on the barber shop floor and I was back in a pirogue headed across the river again. Judging from what I saw in the mirror I am pretty sure I wouldn’t make a great barber. This time I was greeted happily by the same border official. “Very, very good,” he said with a broad smile “Welcome to Senegal.”

Read Part I of this journey: The Call of the Wild

Read Part II of this journey: Adventures in the Sahara