Muammar and Me

I will never forget the day I set sail along the “line of death” with Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi to challenge the US Sixth Fleet. It was January 25, 1986, and it started out like any other day in Tripoli, Libya’s capital, where I was one of about 20 foreign journalists covering a worsening dispute between Colonel Gaddafi and U.S. President Ronald Reagan. The Americans were making threatening noises about Gaddafi’s alleged role in a plane hijacking and two deadly airport attacks.

My newspaper in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, was particularly interested because there were many Albertans working in the Libyan oil fields at that time who theoretically could be in danger if the Americans attacked Libya. The assignment was a total surprise. I was told the bosses planned to send someone else but wanted me to research the quickest way to gain entrance to Libya. No problem. I called around, gave them a rough account of the cost and suggested the chosen reporter fly straight to Madrid, Spain, go to the Libyan embassy there to get a visa, and if successful grab the first flight on Libyan Arab Airlines direct to Tripoli. Then I went out for lunch. When I returned the city desk secretary quickly approached me and said, “Tom, they’re sending you to Libya tomorrow morning.”

Huh? What? Me?

I groaned a for a second and then thought, okay, I could have used a LOT more prep time but it would surely be an exciting and challenging experience to see Gaddafi in the flesh and report on what could turn into a major world story if America bombed Libya. I spent the rest of the day researching Libyan history and politics, printing out copies of stories to read on the plane and trying unsuccessfully to convince my new English wife that I had no choice about going and wouldn’t be in any danger.

I went to the Libyan embassy in Madrid and my first visa request was rejected. I literally pleaded with the Libyan official to ask his bosses to reconsider. You would have begged too if you were stuck with the incredibly lame, painfully vague story ideas about Spain I was assigned to write to cover my boss’s butt if I couldn’t get into Libya. To my surprise and joy the Libyan officials not only granted me a visa a few days later, but added I would get a one-on-one interview with Gaddafi. My big mistake was telling my bosses about the interview because as soon as I got to Tripoli the next morning and met other journalists I learned that every reporter was told that they would get a personal interview with Gaddafi and very, very few ever got it. Those who did were either TV network crews or major newspapers like the New York Times. Nevertheless, I repeatedly pressed our Libyan media handlers for the promised one-on-one interview with Gaddafi, and at their request even submitting written questions. It was a long shot but if I got the interview it would be a major coup for my newspaper. And me.

All the foreign reporters were pressured to stay in Tripoli’s Grand Hotel (aka Al-Kabir Hotel) so Libyan agents could keep an eye on us and listen in on our phone calls. I vividly remember one weekend editor at my newspaper asking me during a phone call if I had been physically close to Gaddifi yet. Yes, a couple of times, I replied. “How did you stand the smell?” he asked, with an idiotic giggle. I was so shocked that I almost dropped the phone. I laced into him hard, emphasizing that all of our calls were being monitored. I also wanted those listening to know that I did not share his idea of a joke. Even now, after all these years, I do a slow boil whenever I think of that imbecile.

My assignment was to visit the Alberta oil field workers, document their concerns and assess what, if any, danger they were in. Unfortunately, the Libyan government refused to let journalists get anywhere near the oil fields, so I was reduced to stopping anyone on the streets in Tripoli who looked like he might be a Canadian oil worker from Alberta. Too bad I hadn’t brought an Edmonton Oiler’s hockey jersey with me to wear. Or a Calgary Flames one.

After much effort and many, many failures I finally managed to find two, neither of whom was worried at all or willing to give me more than their first name – not exactly the exciting story of fear and danger my newspaper bosses were counting on. Libya’s foreign secretary, Dr Ali Trieki, told a news conference I covered that foreign workers, including Americans, would not be held responsible if the US launched a military strike. He noted that no foreign workers were mistreated in 1981 when US planes shot down two Libyan war jets in the Gulf of Sidra. The Americans were taking no chances, however, setting a deadline of February 1st for their citizens to leave the country – a broad hint that they were likely to do something eventually. But when? And what? Obviously, Libya badly needed many skilled and experienced foreign oil workers, the vast majority coming from the US and Canada, and they would have trouble getting many to come if they retaliated against them for actions they had nothing to do with. Terry Ferns, principal of the Oil Company school in Tripoli, which employed 38 Canadian teachers, said he was not worried about retribution against the teachers, and the Canadian Counsel, Denis Gregoire deBlois, told me “We’re not advising Canadians to leave,” all of which I reported. “Nobody’s packing their bags, let’s put it that way,” said one Canadian living in Tripoli. “We don’t feel threatened by anything or anyone really.”

I was not going to sex up the story to please my bosses, who also wanted me to write in the first person and billed me on the front page as “Our Man in Gaddafi’s Camp” with a doctored photo of me as a giant towering over Tripoli’s skyline like the movie poster for Attack of the 50 foot Woman. All this struck me as both embarrassing and amateurish. I dug up everything I could find about the Canadian workers, solicited the help of the Canadian Consul to find me Canadians of all kinds to talk to and wrote many stories about them, but simply ignored repeated management requests to write in the first person, which no doubt pissed them off.

The oil workers angle was largely a bust, so I searched for other stories to do and found three front page ones. I spent about 20 minutes doing a one-on-one interview with the famed international activist/terrorist, George Habash, a Palestinian Christian who was the long-time leader of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). Habash talked at length about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and described how the Israelis had forced down a passenger jet flying over their country the day before, hoping he was on it. “Maybe Israel thought they would get a big fish,” he said, laughing. I also managed to gain entry to a Libyan prison to interview an Edmonton oil worker, Sam Mirasola, who was caught smuggling a few grams of hash into the country and received a three-year sentence. In the two years since then he had learned to speak fluent Arabic, converted to Islam and changed his name to Mohammed Abdessalem Mirasola. I ended up writing two stories about his experience, one describing his personal transformation and the other emphasizing his unhappiness with the Canadian government’s lack of support. I have always wondered whether his religious conversion was real.

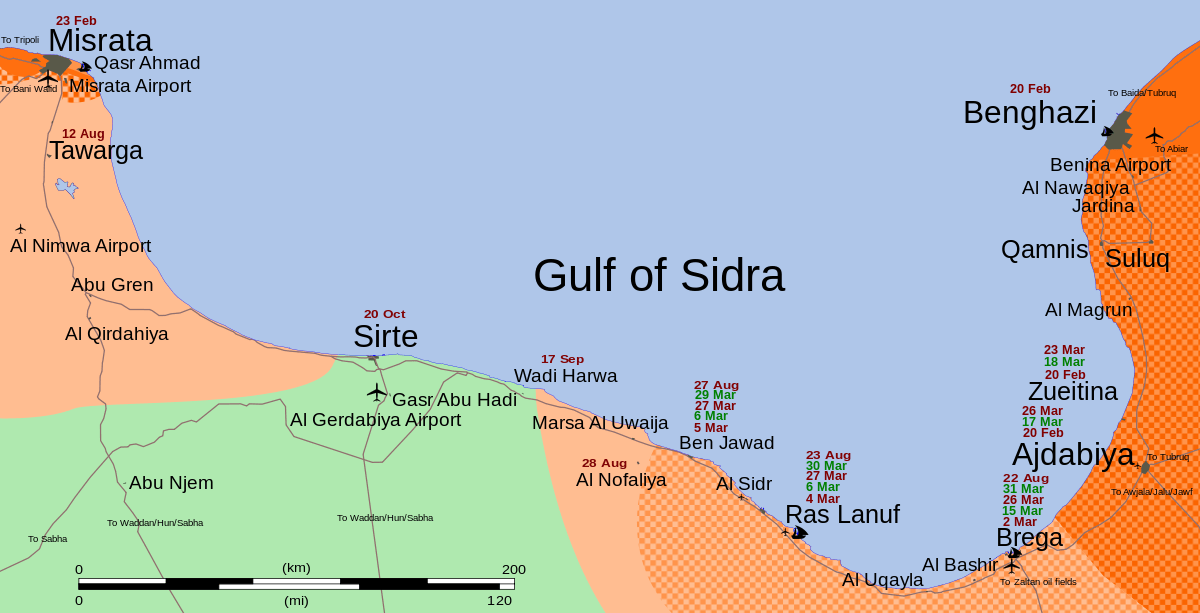

The major hard news development in my time in Libya was the US Sixth Fleet provocatively conducting naval and air manoeuvres on the edge of the Gulf of Sidra, essentially 150,000 square miles of sea between the Libyan cities of Misrata and Benghazi that Gaddafi claimed were all Libyan waters. The law of the sea limits national waters to 12 nautical miles (or 22 kms) and much of the Gulf of Sidra extended far beyond those limits. Almost all the foreign journalists were in the Grand Hotel lobby one otherwise quiet day when Libyan press officers suddenly herded us onto a bus and refused to tell us where we were being taken. We didn’t have to go, but didn’t dare miss what might be an important story about the volatile dispute.

On the bus I sat next to Judy Miller of the New York Times, a very sharp, well informed woman I had talked to a few times in Tripoli and admired. Four days later, after the Challenger spacecraft disaster on January 28th, she told me about being summoned to Gaddafi’s tent encampment so he could offer his comments on the explosion to New York Times readers. I was pleased when Judy won a Pulitzer Prize in 2002 and very disappointed when her career cratered a few years later over her stories about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq that turned out to be inaccurate.

The bus deposited us at the Tripoli Airport and we boarded a Libyan military aircraft, still having no idea where we were going. The plane flew for about 40 minutes, mostly over the Mediterranean Sea, and landed at an airport in Misrata, the port city on the western edge of the Gulf of Sidra, about 200 kms east of Tripoli. Surely this strange trip must be connected to the US military exercises, I thought and hoped. We were all given an extensive tour of a heavily armed 350-ton, missile-carrying Libyan patrol boat, the Wamid. It was interesting but not exactly a great story on its own. We were then led off the boat and expected to be flown back to Tripoli with only a minor story to tell. Surely there had to be something more, we said to each other, all hoping that Colonel Muammar Gaddafi would arrive and save the day with some colourful behaviour. To make this a major international story we needed some provocative remarks from the fiery Libyan leader. Suddenly a fleet of very expensive official cars arrived and out of a massive limousine stepped the man himself.

Gaddafi boarded the patrol boat, splendidly dressed in a royal blue jump suit trimmed in emerald green, wearing a navy captain’s hat and wielding a green swivel stick. Oh, he looked sharp. To our surprise he stood above us on the deck of the patrol boat, looking down and suddenly asked, in perfect English, if we had any questions before switching to Arabic and using an interpreter. He announced that he would sail in the patrol boat along parallel 32.5 which essentially runs from Misrata to Bhengazi. Gaddafi referred to it as “the line of death” claiming his patrol boat was ready to take on the entire US Sixth Fleet. “We shall stand and fight with our backs to the wall,” he proclaimed grandly, adding that the US military exercises were “an act of terrorism”.

I have to give Gaddafi credit – he put on a great show. This was turning into a great story, even if it was mostly just talk. It started to rain and Gaddafi was too far away to rely on a tape recorder, but it was also a real challenge to accurately write down his best quotes with a soggy notebook and pen. Gaddafi accused President Reagan of “playing with fire” and insisted any US war vessel that crossed parallel 32.5 was fair game for his patrol boats. Then he turned away and a short time later the Wamid, with Gaddafi aboard, left to take on the Sixth Fleet, theoretically anyway, while Libyan revolutionary guards waved their fists and chanted slogans as the boat sailed away.

I got a major adrenalin rush from the whole experience, but it wasn’t over yet. The journalists were then all invited onto Gaddafi’s luxurious British-made private yacht, the Farah, and shown around. To our surprise the yacht suddenly set sail, speeding off into the Gulf as we were informed by a Libyan official that we too would also be sailing along the line-of-death with Gaddafi to confront the US Sixth Fleet. Wait a minute. I didn’t sign up for this. I didn’t want to confront the Sixth Fleet! The whole event was becoming surreal. The other reporters also looked at each other in disbelief. Surely this was just more bombast, but in Gaddafi’s Libya anything was possible.

It was then announced that we would all be treated to a luxurious dinner on the yacht and as we sailed merrily along the line-of-death, expensive plates and cutlery were laid out on huge dinner tables – as in The Last Supper. Chaos reigned as the boat cut sharply through the heavy waves at high speed, as we supposedly followed Gaddafi’s heavily armed patrol boat, not that I could see it from the deck. The seas were very choppy and a couple of the waiters on board appeared to become seasick. To my great joy the yacht suddenly turned very sharply around and headed back to Misrata. No explanation was given. A huge table was turned over in the chaos and the plates and fancy silverware went flying. I have no idea what became of Gaddafi and his patrol boat that day but there was no confrontation with the Sixth Fleet.

We arrived safely back at the harbour, boarded the military plane to Tripoli, roughing out the story as we flew and notifying our bosses when we reached the hotel that we had a very colourful story for them. I ran into the Middle East reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer, who was not at the Grand Hotel when we left and found himself in a very bad spot, having missed the biggest story in weeks. Thanks to the eight-hour time difference I had plenty of time to write and file mine, so I agreed to share my notes and visual descriptions with him, earning a new friend, who gratefully invited me to share his extensive library of books about Libya, which proved very useful for later stories. Frankly, I would have happily done it for a thank you, as I was hardly competing with the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Back home in Edmonton my wife watched CNN that night, and smartly slapped a video cartridge into our VCR, capturing the top story on the network, which was Gaddafi’s snappy little show on the deck of the patrol boat and his threats against US forces. The TV camera then cut to a couple of reporters madly scribbling away in the rain as Gaddafi spoke, with your correspondent front and centre. I had great fun watching that video when I got home. I intended to save it forever, but accidentally taped a hockey game over it one night. Damn!

When I arrived back in Edmonton about a week later I noticed that there was something wrong with the rolls of film I shot in Libya. They seemed to weigh nothing. As I later surmised, the night before I left some Libyan security officials must have broken into my room and took all the film I shot, leaving only the empty cartridges. Talk about Spy vs Spy. There went all my close-up photos of Gaddafi. I also was told by someone in the know that the only reason the newspaper even sent a reporter to Libya was that our publisher bet the head of Southam News Services, the company’s national and foreign bureau of reporters, that he could get one of his reporters into the country. I hope he was happy. I certainly enjoyed the experience.

About six weeks after I left Libya there was a bloody confrontation in the Gulf of Sidra between US fighter jets and some Libyan patrol boats, in which 35 Libyan sailors were killed. It was a ‘line of death’ in the end, but Libyan deaths. The following month US fighter jets, responding to a terrorist bombing in a West Berlin discotheque the Americans blamed Libya for, bombed the Tripoli airstrip at 2 a.m., plus an army base and Gaddafi’s tent compound outside Tripoli, killing 45 Libyan soldiers and a couple dozen Libyan civilians, narrowly missing Gaddafi, who was allegedly tipped off just before the raid. One American jet was shot down over the Gulf of Sidra, killing two US soldiers. None of these events had any effect on Albertans or other foreigners working in Libya’s oil fields, of course. Did the publisher of my newspaper really think that the US military would bomb Libyan oil fields full of foreign workers? Or indiscriminately attack Tripoli? At least he won his bet. Or rather I won it for him by virtually begging my way into Libya. Despite the nonsense it was a wonderful experience and a terrific journalistic challenge to cover what was, at times, one of the biggest stories in the world. And to sail along the Line of Death with Muammar Gaddafi.