Only in America

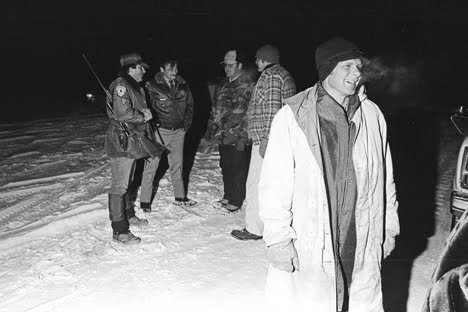

There are many absolutely crazy events that only seem to happen in the United States of America. Where else could you find a grizzled father-and-son, self-styled mountain men living wild in the Montana back country, yearning for years for an attractive young ‘mountain bride’ to kidnap and share? What are the chances they would go hunting for her one day in 1984 and spot gorgeous, young, world-class biathlete Kari Swenson jogging in the woods, grab her by force and chain her to a tree? Then shoot her in the chest the next day and murder one of her would-be rescuers, before heading out into the deep woods with a massive, old-fashioned posse hot on their heels? Only in America would a bronco-busting county sheriff with a Hollywood name like Johnny France track the heavily armed men for five months and finally capture them single-handed in a December snow storm without firing a shot.

In typical American fashion, France tried to parlay his new-found fame into full-scale celebrity status, sifting through book deals and movie offers, and suggesting Clint Eastwood should play him in the film that never got made. Finally, where else to hold that strange trial but in the old courthouse in the former wild west town of Virginia City, Montana, birthed in an 1860s gold rush, with a Boot Hill cemetery packed with the remains of ruthless outlaws who were hanged for robbing and murdering gold miners. The story was one part Deliverance, one part The Collector and one part The Searchers.

In short it was the kind of amazing and tragic story that every journalist wishes to cover, apart from the fact it was occurring in another country and had no direct connection to Alberta or Canada. The only reason my Edmonton newspaper even considered sending a reporter to cover the trial was that a spectacularly strange, dramatic and colourful tale like this one could turn into what journalists call a classic ‘water-cooler’ story – the kind that readers across the city would be gabbing about at work, at lunch or literally around the water-cooler. Would it be less interesting to Edmonton readers because it happened in Montana? Would our readers identify with the victim less because she was an American? Would the paper showcase the story or bury it in the back pages? I was very surprised to hear we were sending someone to cover it, but pleased that I was the one they chose to go. It was definitely a Tom Barrett story. I quickly agreed, but soon realized there were serious practical problems. I did not have a driver’s license back then and my research established that a plane and a bus could only get me to a town 60 miles from Virginia City. Besides, the only accommodation left was more than 10 miles from the courthouse because the US media hordes were booking every room or cabin in the general area. Even if I got a room there was no public transport to Virginia City. So I asked to opt out and my bosses reluctantly accepted.

I went back to my desk and started thinking hard about what I had just done. Next thing I knew I was giving myself a lecture. Sure, this assignment could turn out to be a massive pain in the ass to arrange, but even if I had to hitchhike the final 60 miles, plus back and forth to the courthouse every single day, I should just grab the damn thing before someone else did. It was a terrific, if tragic, page-turner of a story, a wonderful opportunity and a guaranteed great experience even if my stories got buried in the back pages. There was nothing to lose by acting boldly and everything to lose by taking the easy way out. I hurried back to the city desk and told them I wanted the story and I would find a way to make it work. They were pleased. Happily, the city desk secretary soon found a small motel in Ennis, Montana, 14 miles from Virginia City, whose owner offered to drive the 60 miles to pick me up and ferry me back and forth to Virginia City during the trial for a few extra dollars. I was on my way.

As a Canadian criminal justice specialist I was used to local closed-mouth prosecutors and police officers, plus very few judges who would talk to a journalist. Not in the USA. There, EVERYBODY talks to the media and no one worries about denying the accused a fair trial. On my first day in Virginia City, May 7, 1985, I was invited to lunch by Madison County Sheriff Johnny France. The 46-year-old cowboy was happy to tell his tale of the crime and the arrest and noted that he had been contacted by multiple movie and TV officials. We discussed all the possible star actors who could play him in a film or made-for-TV movie and he mentioned that he had hired a personal manager, a lawyer and an accountant. This was France’s one big shot at fame and glory and he intended to grasp it with both hands.

Only in America.

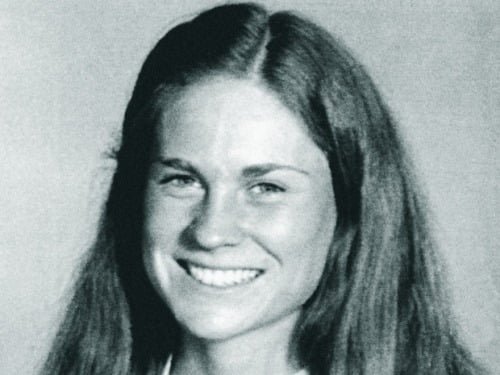

The first major prosecution witness was Kari Swenson, who wept openly as she re-lived her 17-hour nightmare confrontation with the so-called mountain men, Don Nichols, 54, and his son, Dan, 19, on July 15th and 16th, 1984. The younger Nichols was on trial for murder, kidnapping and aggravated assault, with his father scheduled to be tried on similar charges four months later. Swenson described how the filthy, unshaven men slapped her around, chained her to a tree like a dog, and left her bleeding from a sucking chest wound in the cold wilderness after Dan Nichols shot her, apparently accidentally, when two men from a massive rescue party burst into the Nichols’ camp, the morning after she was kidnapped. The 23-year-old woman described her humiliation at being forced by the self-proclaimed mountain men to remove her shorts, and her shock at witnessing the murder of her friend, Alan Goldstein, who Don Nichols coolly shot in the face.

Swenson described how father and son blocked her on the mountain path she was running on in the Big Sky area near Bozeman, Montana, the day before, and forced her to come with them. “He (Don) grabbed me by both hands and wouldn’t let me go. He said ‘we don’t get enough women up in the mountains we can talk to’.”

Swenson tried to convince them she was a happily married woman, but Dan told his father “Don’t believe her, all women are liars…let’s keep her,” she testified. The elder Nichols hit her in the face and wrestled her to the ground, twisting her neck when she called for help, Swenson added bitterly. “The old man told me not to cry out again or he’d beat me up. He said he’d give me two black eyes and just because I was a woman that wouldn’t stop him.” Clearly these two ruthless clowns were not mountain men, just a pair of ignorant bullies that some locals shamefully chose to mythologize, which deeply angered Swenson, her friends, family and all decent people.

They said they wanted female companionship and would kill anyone who tried to rescue her, Swenson told the court, adding that Dan remained unmoved by her desperate pleas to be released. “I begged him to let me go. I told him I didn’t want to be there. I begged him over-and-over again, but it didn’t seem to faze him. I started crying and was close to being hysterical. He said, ‘No, I want to keep you. You’re pretty.’”

“I want to keep you. You’re pretty.” – Dan Nichols

Swenson said the next morning tragedy struck when her friend Alan Goldstein arrived at the camp with another man searching for her. “I started screaming and yelling at him to watch out because they had guns.” Don Nichols told his son Dan to shut her up and she was still looking at Goldstein when a point-blank shot in the chest lifted her off the ground, she said. “I started screaming ‘Help me, I’ve been shot. Somebody help me’.”

At that point Dan knelt down and said something about not meaning to shoot her, Swenson testified. Goldstein then pulled a gun from his pack, went behind a tree, and told Don Nichols they were surrounded by 200 armed men, she said. “The old man raised his rifle, aimed it and shot Al,” Swenson told the hushed courthouse. A second rescuer, James Schwalbe, ran for help and the father and son left, ignoring Swenson’s pleas that they leave her the sleeping bag to help her survive the cold.

Her sight and strength failing, and blood gurgling in her wounded lung, Swenson crawled on her belly to the smoldering fire in a desperate search for warmth. “I was in shock,” she said, tearfully. “I thought I was going to die.” Somehow, she overcame the overpowering urge to sleep for four long hours, until a rescue party arrived to find her semi-conscious and rushed her to a hospital. Swenson cried frequently as she described her ordeal in a soft but steady voice. I believe it was the most dramatic, moving and totally convincing testimony I ever witnessed. It was followed the next day by some of the least convincing testimony I have ever listened to. The other journalists I talked to, all of whom were Americans, read it the same way.

“I thought I was going to die.” – Kari Swenson

Don Nichols clearly sacrificed himself on the witness stand the next day. It was an attempt to protect his son by taking virtually all the blame for the kidnapping and murder. It just lacked the ring of truth. Of course he was the driving force behind the kidnap scheme but Dan was fully engaged in it. The father basically accepted the prosecution’s narrative but minimized his son’s role in the crimes. Dan’s lawyer prefaced the father’s testimony in his opening statement by claiming that the old man made all the decisions and the son was a virtual prisoner of his father’s dreams of a mountain life together. Don Nichols admitted he didn’t believe in the law and pulled his son out of society for long periods “because I don’t believe in schools. I provided a few facts of life that schools seem to suppress. There are certain things that are done in the mountains that don’t make sense to other people, but up in the mountains they do.” He burst into tears repeatedly while describing how Dan’s pet coyote died and the 14-year-old boy ran away from him. But he had no tears or sympathy for Swenson or Goldstein, which tells you all you really need to know.

The father testified that he had been planning on forcibly taking a woman to the mountains for many years and in 1978 he purposely bought the chain he used six years later to tie Swenson to a tree. He said he tried to calm her down after he grabbed her wrists, but she kept panicking. “I told her I wasn’t going to rape her and all that stuff. She kept mentioning her friends. I said you just better hope they don’t try anything or I’ll shoot them.” Under cross examination he testified that he didn’t snatch Swenson just so his son could have a mountain bride. He said he also wanted the “good looking” young woman for himself. “The girl was for both of us,” he asserted.

“The girl was for both of us.” – Don Nichols

Don Nichols said he and his son were both lonely in the mountains and they went to the Big Sky area of Montana in July, 1984, specifically to kidnap a woman and take her back to their mountain camp. His son saw Swenson jogging up the trail and told him there was “a hell of a pretty girl coming,” the father testified. Swenson said earlier that the father expressed disappointment she wasn’t older. “I said ‘well then, why not let me go?’ He said ‘No, we’ll keep you. You can decide on one of us.'” Fortunately for Swenson the rescue attempt which freed her came before father or son had time to force their sexual desires on her.

The elder Nichols chafed under cross examination. “I don’t care what people like you think,” he snapped at prosecutor Marc Racicot. “What solid, decent people think, I care a lot about.” He defended the fact his son was carrying marijuana when he was arrested. “I think every generation should have their own vices. If they didn’t they’d probably end up killing guys like you.” He admitted living by his own set of natural laws in the mountains, but refused to discuss them. “My secret way of life is none of your business,” he said. “We do a lot of things we don’t want people to know about. We don’t like snoops.”

The following day Kari Swenson’s mother, Janet, raced from the courtroom in tears as Dan Nichols described how he shot her daughter in the chest. The young defendant also broke down at this point, but regained his composure a few seconds later. He insisted that the shooting was an accident and blamed his father for the kidnapping. Dan Nichols said that Swenson was shot during the chaos that erupted when the rescuers, Alan Goldstein and James Schwalbe, stumbled upon the Nichols’ camp. “Kari Swenson was only a couple of feet away, I never pointed it (the gun) at her. She screamed ‘they’ve got guns’ (to the rescuers). When she screamed I just looked at her. I turned to look at Schwalbe and pulled the gun with me. It’s got a hair trigger and it went off.”

After the final arguments from the lawyers and the judge’s charge to the jury it was time for the deliberation and the verdict. It was a long wait. Nighttime came, but the deliberations continued. I just hoped it wouldn’t drag on for days. My fellow journalists and I stood out on the courthouse steps that evening swapping stories and speculating about the jury verdict. To my surprise Montana District Judge Frank Davis came out and joined us, offering his own speculation about when the verdict might come and just chatting about the trial. Only in America. After deliberating for 11 hours the jury found Dan Nichols not guilty of the murder of Al Goldstein, guilty of kidnapping and assault on Swenson, not of aggravated assault, suggesting the jury was not convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that he shot her intentionally.

A few weeks later, long after I came back home, Judge Davis sentenced Dan Nichols to 20 years in prison. He was paroled after six years but has not managed to stay out of prison. He was arrested for possession and sales of illicit drugs in 2011, skipped bail and was finally captured in Butte, Montana. This time he was sentenced to four years in prison and served two. Don Nichols was tried in September 1985 and received an 85-year sentence for murder and kidnapping, serving 32 years and finally being granted parole at the age of 86 on April 26, 2017. Sadly, Swenson, who was enraged by Don Nichols’ parole, was never able to fully regain her world class biathlon form, largely because of painful bullet and bone fragments in her lungs. She is now a veterinarian in Bozeman, Montana.

Johnny France, the former rodeo star and media darling got invited to the White House for the second term inauguration of Ronald Reagan, was given the key to the city of Tulsa, Oklahoma, and named an honourary Oklahoma Territorial Marshall. He also went on tour promoting his book, Incident at Big Sky, but his role was largely ignored in a made-for-TV movie about the kidnapping and murder. Worst of all, much of the local community was angered by France’s cultivation of fame and voted him out of office in June, 1986. The voters preferred his deputy, Dick ‘Sparky’ Noorlander, apparently concluding France spent too much time bragging and touring. “I think some people maybe thought I was just too big for my britches,” France told a Chicago reporter. “But it really hurt.”

I came home, thinking that was the end of the affair, until a manager approached me a few months later and asked if I could find out when the trial of Don Nichols was scheduled in case they wanted to send me back to cover it. I was shocked that would even be considered, but I dutifully looked up the phone number for the Virginia City courthouse and dialed it. To my amazement Judge Davis answered the phone. I told him I had covered Dan Nichols’ trial and asked when his father Don’s trial would begin. He said he remembered talking to me, gave me the trial dates and strongly suggested I should not miss it. “You should really come,” Davis said. “It’s going to be a great trial.” I told him I’d love to cover it, but it was up to my bosses, who understandably didn’t send me as the second trial would surely be largely a repeat of the first one. Judge Davis said if I came I should call him, saying we’d go out to dinner and have a great time. I didn’t doubt it, but couldn’t imagine having that kind of conversation with a Canadian judge, even those I came to know and like.

Things like that only happen in America.