Mountains of Mystery

There is no place on earth like the Mountains of the Moon. The gigantic vegetation that lines the alpine meadows, great bogs and valley bottoms of the fabled Rwenzori Mountains, and the majestic beauty of its great snow peaks shining through the constant mist have inspired many an intrepid traveller to poetic imagery. There is nothing to break the spell, nothing to dim the sense that one has journeyed back in time to a forgotten, almost primitive world, where the only sounds are the steady drip of rain and the solemn plodding of one’s own footsteps. A world that is home to no man. Or woman.

The search for the Mountains of the Moon is part of one of Africa’s greatest adventure stories: the quest for the primary source of the great Nile River. The names of the Rwenzori’s individual mountains read like a roll call of Africa’s greatest explorers – Stanley, Baker, Speke, Gessi, Emin, di Savoia – men who braved deadly sickness, sometimes hostile natives and treacherous unmapped country in search of the unknown, including the mythical peaks at the foot of the Nile referred to by the ancient Roman geographer, Ptolemy.

I felt some of that mystery and romance in 1984 in Uganda as I waded through the thigh-deep sludge in the Lower Bigo Bog, and gazed at the unearthly and gigantic vegetation for which the Rwenzori range is famous. My thoughts turned to the bold explorers who first shivered in the rainy mist and battled the rugged terrain to reach this wild spot. How they must also have stared in awe at the spectacular vistas. Some described it as a kind of enchanted forest, where thick layers of lichen called ‘old man’s beard’ smother every branch in the dense thickets of seven-metre tall tree heather creating a ghostly atmosphere, where eight-metre spikes of giant lobelia reach for the sky like long green fingers, and where 10-metre tall giant groundsel, crowned with cabbage-like leaves, tower over everything.

Exhausted but exhilarated, I walked on that day behind my trusty BaKonjo guide, Saulo, who had led trekkers through these trails for 27 years. Using a walking stick and following Saulo’s lead, I tried to manoeuvre around the thick mud, leaping desperately from one giant one-metre high tussock of carex sedge to another. Unlike my nimble-footed guide I occasionally lost my grip and slid down into the quagmire of the bog’s deep mud, which soon covered me from head to foot. It turned into a crazy mud bath and I ended up totally filthy, but I loved the experience. Besides, I had a change of clothes. I was deeply disappointed to learn years later that a crude boardwalk had been built through the Lower Bigo Bog, making crossing it an easy 20-minute stroll instead of an authentic 90-minute slog. I’m just glad I got to share a bit of the adventure of wading through that giant swamp that the initial explorers experienced.

Then we encountered the rarest sight of all in the Rwenzoris – a man alone. Sloshing through the bog in his bare feet, an old hunter dressed in a black and white colobus monkey skin and using an enormous spear for a walking stick appeared suddenly out of the mist, smiling broadly. To my surprise he walked up to Saulo and gave him a warm embrace. My guide explained that this was his 60-year-old uncle, coming home with a pouch-full of skins from antelope and hyrax, sometimes called the African rock rabbit. After gratefully accepting a handful of waterproof matches from me, the old hunter melted back into the swamp like an apparition while we trekked on to the mouse-infested Bujuku Hut at 3,962 metres (13,000 feet).

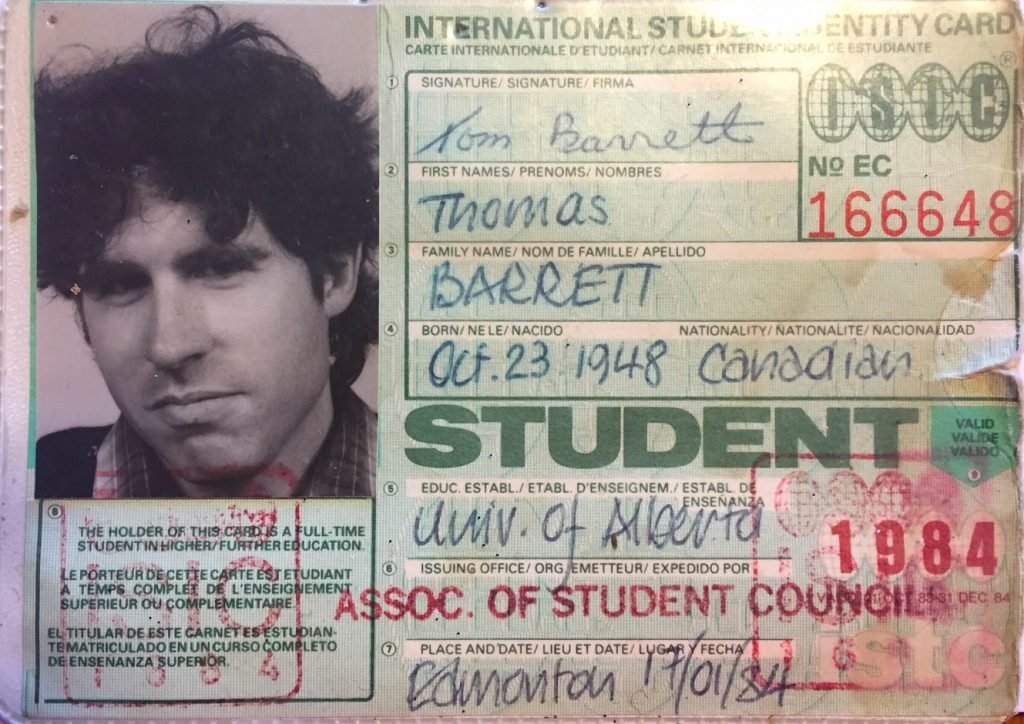

The night before, Saulo, my two porters, and I warmed ourselves around the fire under a huge rock shelter and rediscovered the truth that music is magic. The three BaKonjo tribesmen were fascinated when I conjured up a news program with my small transistor radio, and their response was ecstatic when I tuned in to some scratchy African rock music. Crowding around the little radio they sang and juked to the music in unison. Saulo translated the song for me as he spun an imaginary dance partner around the fire. “I love you my darling you must love me too,” he crooned. “Come, you will be my wife.” Later, as we sipped sugary tea around the fire, Saulo asked why a 35-year-old man like me had no wife or children. “I have two wives and eighteen children and I want more,” he said proudly. “Now, when I die everything will be taken care of.” He had a point I guess, but I ultimately ended up settling for one wife and three children.

Despite their natural beauty and botanical importance, the Rwenzori Mountains remain one of the trekking world’s best kept secrets. Locked away in the dark heart of Africa, and shared by two of the continent’s most troubled and violent nations, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, they offer the adventurous traveller a chance to hike into wild, untamed country, see plants that would not look out of place in a science fiction film, climb snow peaks that soar 5,000 metres over the steaming jungle forests and catch a glimpse of Africa as the first explorers found it. The circuit hike of the Rwenzoris was one damn tough trek, but the rewards were deeply satisfying. I was one of only 150 trekkers who walked the Rwenzori circuit that year, mainly because Uganda was in the middle of a vicious civil war. Today about 2,000 people each year take on one of the now two week-long circuit hikes. By contrast 50,000 people each year visit Mt. Kilimanjaro.

Although the ancients had intimations of its existence, and the Roman geographer Ptolemy included certain Lunae Montes in a rough map of Africa, the Mountains of the Moon were not discovered by the white world until 1888, when Henry Morton Stanley, the man who found Dr. Livingston, spotted them looming through the mist south of the Congo’s Lake Albert, just as I first spotted them in 1982 looking north from Lake Edward. A young boy drew Stanley’s attention to the range, telling him the mountains were covered with salt.

“Peak after peak struggled from behind night dark clouds….until at last the snowy range, immense and beautiful….drew all eyes and riveted attention, while every face seemed awed,” wrote the great explorer. Stanley applied the BaKonjo name ‘Rwenzori’ (Place of Snow) to the peaks, which receive more than 300 cm of precipitation a year. I purposely went during the January/February ‘dry’ season, but it rained for hours every day anyway. I could only imagine what the ‘wet’ season must be like.

In 1984 little had changed in the Rwenzoris since the days of the early explorers. Porters were still paid little to carry as much as 22-kg loads up some of the roughest, steepest trails in Africa, but the long tradition of buying sweaters and blankets for the men was still in place. Arrangements for guides and porters were made at the Ugandan village of Nyakalengija, where John Matte, whom the other BaKonjo called simply ‘The Chairman,’ ran the show, as he had for many years. I purchased the traditional required supplies at the outdoor Nyakalengija market the day before the trek began. With the assistance of Saulo and a local boy I bought 14 kgs of cassava flour, 1.8 kgs of groundnuts, 900 grams of sugar, 540 grams of salt and 90 grams of tea, plus cooking pots, blankets, sweaters, two pangas (machetes) for path cutting, three packs of English cigarettes and 24 smoked fish. I had a palpable sense of participating in an ancient ritual by preparing for an old-style expedition. For myself I brought from home packets of dried soup, ready-made dinners to heat up over my small stove or on the charcoal fire, porridge and a fistful of chocolate bars.

After months of training and preparation, numerous attempts to explain why I was making the trip, and a rude shakedown by Ugandan immigration officials, it was a tremendous relief to set off on the trail at last. There was a blissful sense of being swallowed up by the jungle as the path grew progressively fainter and the vegetation much larger and more exotic. It was as if each step took me farther and farther away from the world of modern civilization into a wilder, purer existence.

On the first day we hiked through the tall elephant grass and evergreen trees of the montane forest zone into thick bush populated by swarms of colourful butterflies. After two hours of vigorous walking we forded the Mahoma River and ended the day’s journey with a brutal ascent up a steep glacial moraine ridge to the Nyabitiba Hut at 2,652 metres (8,700 feet) an elevation gain of more than a thousand metres. It was tough walking but I was thrilled that I was able to comfortably keep up with Saulo and the porters. In the hour before dinner time I was drawn to some animal sounds nearby and watched fascinated as black and white colobus monkeys cavorted high up in the trees. After a year of preparation I was thrilled to finally be on the trail.

The second day was harder as we steeply descended to make the heart-stopping double-ford of the swiftly rushing Mubuku and Bujuku Rivers, which now feature a modern bridge, then climbed nearly 1,000 metres through tangled undergrowth and thick bamboo forest, slipping and sliding over wet branches and numerous jumbled, mud covered boulders that block the narrow path while Saulo expertly wielded his panga, cutting down the immense vegetation on what passed for a trail. It was slow going but this was exactly the challenging experience I was longing for. I was having some trouble keeping up with the porters, however, and asked Saulo if we could take a short rest break as I was out of breath. I told him I was surprised by my exhaustion after finding the first day’s climb rugged and steep but manageable. Saulo laughed, then explained to me that the porters were paid the day before the trek started, partied all night long and got dead drunk on local home brew. They both had terrible hangovers the first day on the trail but were now recovered and going full throttle, he added with a chuckle. After the short break we began a relentless four-hour climb that set my heart pounding, finally reaching the next hut, which was a total wreck. We all cooked and slept under the massive Nyamuleju rock shelter.

We marched on the next day through the Lower and Upper Bigo Bogs to the beautiful Lake Bujuku in the very heart of the mountain range, and for once the weather was lovely. As the rain stopped and the mist cleared, revealing blue skies for about 30 minutes, I stared at the great snow peaks and what some have called the most stunning view in Africa – if you’re lucky enough to get a peek at it. The Bujuku Hut was wedged in the centre of a veritable forest of giant groundsel, under the shadow of The Rwenzori’s troika of great mountains. To the west a massive ice cornice protruded from the spectacular slopes of Mount Stanley at 5,109 metres (16,762 feet), Africa’s third highest mountain. The north offered misty views across valleys to the wilds of the Congo; extensive silver meadows pointed the way to where Lake Bujuku shimmered under the icy fortress of Mount Baker at 4,843 metres (15,889 feet). Turning around I looked up at an ice cave atop the snow-capped pinnacles of Mt. Speke at 4,889 metres (16,040 feet). If the clouds had not returned I believe I would have stared in awe at these magnificent mountain views for many hours. Sadly, the glaciers on these shining peaks are rapidly retreating under the merciless assault of climate change, so get there while you can.

Following tradition I had to pay the guide and porters double the next day to walk through the light snow in their bare feet over the Scott Elliot Pass at 4,372 metres (14,343 feet) between Mts Stanley and Baker. As we neared the top I stole a final glimpse of Lake Bujuku, shining beneath us like a silver bowl. We trekked on over massive boulders and to my surprise Saulo began moving faster and faster, actually breaking into a jog as we descended towards the Kitandara lakes on a very muddy trail. I began running too, not knowing why, nearly turning my ankle as I stumbled and fell over the rocks and slipped in the mud. Eventually I caught up and Saulo grinned mischievously and pointed at a large stone in a small crater at our feet, warning me of the danger of falling rocks. He punched the palm of his hand with his fist to show how the jagged stone had fallen on this spot. “This place very terrible” he added, pointing out more rock craters as we walked on quickly.

Arriving at the Kitandara lakes, the most beautiful setting in the circuit walk, felt like re-entering the world of birds and beasts. It was a delight to watch black ducks floating serenely on Lower Kitandara Lake and white-necked ravens scavenging about. Most prominent were the lovely scarlett-tufted malachite sunbirds which flit from one giant lobelia to another, feeding on the honey and insects in the flower spikes.

After an unforgettable sunset over the lake, the night silence was torn by the bizarre screeching of hyrax, like hoofed rabbits that are improbably distant relatives of elephants. The Rwenzori have long been famous for leopards that ranged to the snow line at 4,000 metres (13,123 feet) and the beautiful big cats remain a prominent feature. I knew the sounds were only hyrax, and that the leopards were rarely a threat to humans, but the combination of total darkness and howling rock rabbits robbed me of sleep until I managed to wedge the hut door fully shut.

The next day we climbed steeply through a giant groundsel forest up to and over the Freshfield Pass at 4,282 metres (14,049 feet) and as light snow fell it turned the very steep downhill path into a mud slide for the entire nine-hour descent back to the Nyabitaba Hut, passing the lovely Kabamba Falls and the Guy Yeoman Hut without stopping, walking two full days in one. After repeatedly falling I switched to sliding on my butt down the steep and slippery slopes, bouncing up and down wildly. I managed to provide some drama by falling on a battalion of stinging army ants with huge pincers. It was more like bouncing than falling as I leaped to my feet howling and everyone raced in to help brush the voracious, swarming ants away. We all swatted them wildly but the next half hour of hiking was punctuated with periodic yelps as one-by-one I pulled off the remaining nasty pests from inside my shirt.

Slowly and very gingerly we dropped down a very steep rock step and carefully continued our descent, fording the potentially dangerous Mubuku River. A Ugandan drowned there six years later trying to make the crossing, leading to a bridge finally being constructed. After another hour we finally reached the Nyabitaba Hut, a drop of 1,630 metres (5,349 feet) from the Freshfield Pass. I was surprised to meet a man and two women trekkers who had just finished their first day on the trail. They were the only western travellers I encountered on the hike.

The end of the journey at Nyakalengija the following day was a time for both celebration and reflection. I happily slurped down copious amounts of homebrew banana beer from wooden bowls with Saulo and the porters, gave them their well-deserved tips and double pay for Day 4, endured numerous jests about the blisters on my feet, my ravaged toe nails, the cuts I’d received from nettles, and the army ant bites on my torso. I couldn’t resist a smile of satisfaction and accomplishment. Good things are hard.

Back at the Hotel Margherita in Kasese I took a very badly needed shower and looked at my beaten up feet before heading downstairs for many rounds of beer. I had made the mistake of wearing huge hiking boots instead of wellington boots, which keep the feet dry. Live and learn. I had already lost a couple toenails and would eventually lose all ten of them. New nails grew back but they were never quite the same. Judging from the six-day beating I endured on the trail, it would be an exaggeration to say I conquered the circuit hike of the Mountains of the Moon. Like Rocky, I’m just proud to say I went the distance.

After an additional day to rest up I flew from Kasese back to Entebbe Airport where there were huge problems getting on the last flight of the day to Nairobi. This terrified me because I was totally unwilling to spend the night in Kampala and didn’t particularly want to sleep overnight at Entebbe either. I was waiting in line, seeing everyone turned away until there was just one man ahead of me. I could hear the officials explaining why he couldn’t get on the plane when he suddenly erupted angrily, telling them he was President Milton Obote’s personal pilot and if they didn’t let him on the plane there would be hell to pay. They waved him on nervously and in a moment of inspiration mixed with desperation I instantly mumbled that I was with him and just kept walking quickly a half-step behind him. Thank God they didn’t call me back. As Machiavelli noted in The Prince, fortune favours the bold.