River of My Dreams

There are some adventurous moments that intrepid travellers occasionally experience which are seared into their memory forever. Moments so exotic, so far removed from their day-to-day life back home, that even decades later those memories seem to jump off the page as if they were written in italics. Chasing such experiences is like an addictive drug for hard-core backpackers, which I certainly was in my younger and not-so-young-anymore days.

The episode I am thinking about occurred in January, 1982, while travelling rough on an old tugboat pushing a couple of rickety barges up and down the great Congo River, as they still do today, though not as frequently. The boat was chugging along very, very slowly upstream from the capital, Kinshasa to Kisangani in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), formerly known as the Belgian Congo. My approximately ten days on the boat were utterly chaotic and wonderful—and kind of grungy. It spurred my memories of reading the journals of the legendary Henry Morton Stanley, who founded Kisangani and found Dr. Livingstone (in the town of Ujiji on the shores of Lake Tanganyika), and great novels set on the mighty river, like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and VS Naipaul’s A Bend in the River. But mostly, they fulfilled my childhood desire to visit the massive green country in the heart of Africa I read about as a young boy in the National Geographic.

I boarded the boat in Lisala, a small, very poor, very dusty town best known as the birthplace of DRC strongman dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko, on the north bank of the Congo River, for a 520 km journey by boat to Kisangani. I arrived in Lisala after a very rough trip riding in the back of trucks for about three days on horrific roads from the village of Zongo, on the shores of the Ubangi River, where you could hear the loud sounds of bellowing hippos at night. I also dealt with a wily young immigration official in Zongo who tried his best but failed to pry a bribe out of me.

This was not like taking a boat in Europe or North America. There was no real schedule and no one knew for sure when the next boat was coming, including company officials, so I set up my tent and camped near the port along with perhaps ten other backpackers. We lived on the very meager supplies available in a local store, while waiting for our boat. A few days passed before a rumour spread that it would arrive the following morning, which it did. I happily climbed aboard the decrepit old ship, chose a spot to sleep near the tugboat roof, put down my non-valuables and went exploring.

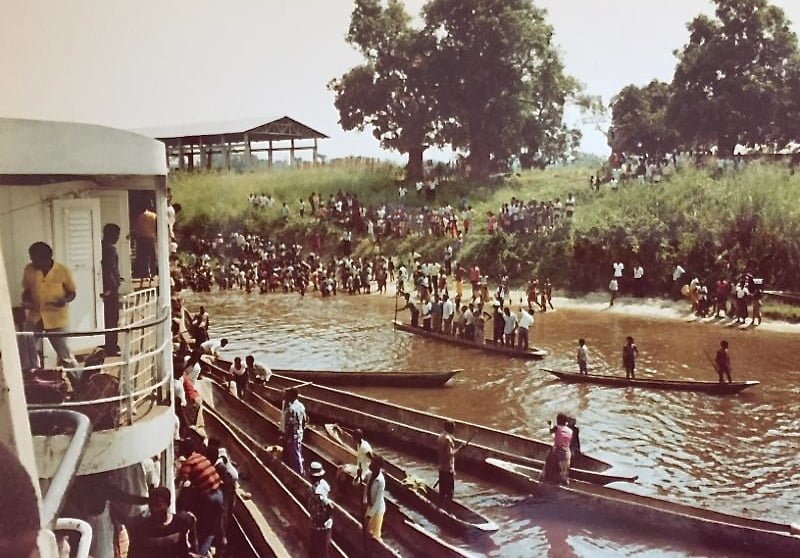

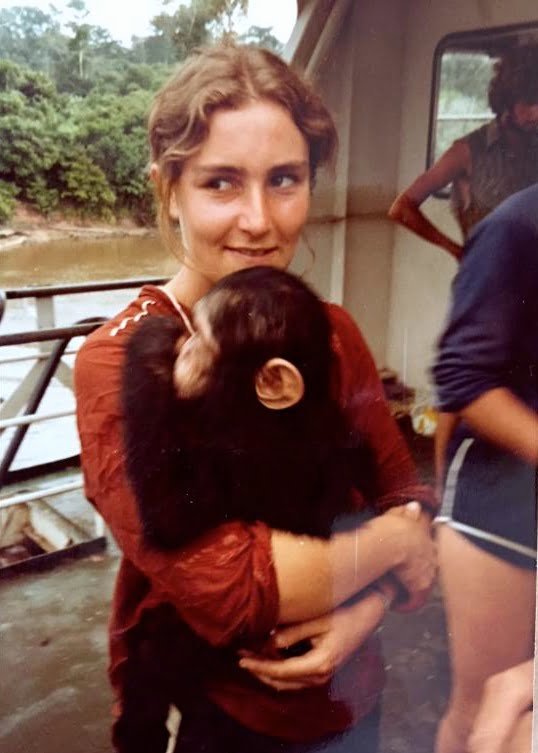

The barges were like very flimsy, floating villages, tightly packed with Congolese people sleeping, shopping or bargaining furiously. Whenever the tugboat stopped, which was very often, dozens of local villagers would quickly flock to the thriving mobile market in their dugout canoes, called pirogues, to buy and trade before the boat left. It was quite a smorgasbord. There were large piles of fried monkeys, huge fish of various kinds, fruits like plantains, mangoes and pineapples, vegetables like manioc and avocados, plus snails, grubs and even baby crocodiles. Yum yum. There was also what you might call crafts or trinkets to buy and sell. Plus chickens and the odd goat. An Australian woman even purchased a young chimpanzee for a significant fee and walked around with it in her arms throughout the journey. I had no idea what she intended to do with the chimp, as she was obviously never going to be allowed to take it out of Africa. In fact, it was taken from her by local officials the minute she stepped off the boat in Kisangani.

About half the backpackers on the tugboat were travelling with a rock bottom, cheap-as-they-come, overland travel adventure company, the name of which I can no longer recall, but temporarily joined up with later. The driver of their massive German truck, an amiable and extremely handy Dutchman, had deposited them in Lisala, so those who wanted to could take the boat, while he drove the other half of his passengers overland to Kisangani on the DRC’s unimaginably horrible roads, generally regarded as the world’s worst. Why anyone would prefer that truck ride to the boat trip is totally beyond me, but the boat tickets cost a bit and I presume that’s why they passed on a wonderful experience. I later learned that many of them were nearly broke, making me, who had more than sufficient money and a good paying job to return to, look like a wealthy man by comparison. I got to know all of them, including the Australian girl with the chimp and a likeable guy from Quebec, whose fluency in French was of great assistance to us all. Our daily meals, which were included in our boat fares, mostly consisted of mystery fish in a bowl of rice with some obscure vegetables. Removing the fish bones took some time and the meal was largely tasteless, but it kept us going.

The tugboat was an aging, rusty wreck, but the bar, where the meals were served, was a hotbed of action. It had a really good sound system and we rocked every evening to the tunes of the musical stars and their bands from Kinshasa, the DRC’s capital, one of the great African centers of popular music. As we crawled our way up the Congo River I grooved nightly to the sounds of Franco, Tabu Ley Rochereau, Mbilia Bel and many others, and later bought cassette tapes of their music, which I played at home until they literally fell apart. I still listen to their music—most of which has a Cuban rhumba flavour, an infectious rhythm, fine guitar work and plenty of horns—on YouTube. They mostly sing in Lingala, so the lyrics are a mystery, but that doesn’t bother me.

The bar also had a seemingly endless supply of ice cold Primus, a tasty pale lager that many old African hands consider their favourite local beer. I sure liked it. Primus was created and brewed by the Belgian colonialists beginning in 1923 in Kinshasa and Kisangani and is still very popular—for those who can afford it. The rest must settle for the crude local moonshine, called Lotoko. Belgium was a horrifically bad colonial power, but they have always brewed some very good beer. Think Stella Artois. I had plenty of cash so I drank lots of Primus, which was very tasty and a lot safer than local water. It was very hot on the boat during the day and a cool beer was a delight. I also bought lots of rounds for the friendly backpackers who were heading from Kisangani by truck through the beautiful but wild eastern Congo down to Goma, on the Rwanda border, the exact route I planned to take. I spent the rest of my time on board either exploring all the weird objects for sale on the barges, as we chugged up the mighty river, or gazing at the massive, endless jungle on both sides, interrupted only by the occasional primitive village from which a flotilla of pirogues always emerged as we stopped. Hot as it was on the boat it was cool near the roof where I slept and contrary to my expectations I don’t remember being bothered by mosquitos or other annoying critters. After a few days we stopped to pick up passengers and supplies at Bumba, 400 km from Kisangani.

I distinctly remember the final night on the boat as gently warm and magical. I walked out on the deck after dinner, as darkness fell, jiving to the hypnotically powerful music from Kinshasa blasting out of the speaker system, with a bottle of cold Primus for company. There were a group of Congolese soldiers on the deck who came aboard at Bumba and were on their way to Kisangani. I noticed the soldier next to me light up a huge joint, filled with some rocket-powered Congolese grass. I hadn’t smoked a joint in a few years, let alone anything this potent, but a voice inside me whispered that this was an opportunity I should not pass up. The friendly soldier handed the joint to me and I inhaled as deeply and as long as I could hold it in, before slowly exhaling and passing it back to him. He only smiled and held up his palms, signaling that this joint was all mine. I nodded in gratitude, then walked to the edge of the deck, holding the bottle of Primus in one hand and the super joint in the other, alternating deep drinks and long tokes as the old tugboat churned up the timeless river, passing villages with massive bonfires burning and the pounding of drums as people danced wildly beside the shore. I felt like I had been magically transported back to another, much older and simpler world. I have no idea if these were special celebrations or nightly occurrences, but the entire experience was so primal and dream-like that I wondered for a second if it was real, and if I ever would be able to explain to anyone back home what it felt like to witness such an astonishing spectacle. That night—standing on the deck, in the heart of wildest Africa, filled with wonder and awe and rocket-powered Congolese grass—is one of the clearest memories in all my travels.

The next afternoon we arrived in Kisangani. After port officials took the Australian woman’s chimpanzee away, we were told we would have to pass through immigration—which was total nonsense. Each one of us had a valid visa stamped into our passports, and each of us also had an entry stamp obtained at the DRC border, which confirmed that we could legally travel in the country for weeks longer. The officials argued unconvincingly that there was some kind of special stamp that we all needed but none of us had. Our man from Quebec was the only one of us who was sufficiently fluent in French, so he carried on the spirited negotiations, occasionally updating us. They kept insisting we all pay a huge fine, which we refused to do. The shakedown lasted for well over an hour as our Quebec spokesperson wore them down. The size of the desired fine kept dropping until finally one of them blurted out in French “Can you at least give us enough for a couple rounds of beer?” We accepted that offer gladly and finally entered Kisangani. The other backpackers were not so lucky. Their government interrogators literally put them in an appalling jail cell when they wouldn’t fork over the desired cash. I don’t know how long they were stuck there, but I did see one or two of them walking around Kisangani before I left, so they must have reached an agreement of some kind. What I should have realized at the time, but didn’t, was that the immigration officials likely hadn’t been paid in months, like some school teachers and other officials I met earlier. They had families to feed and I’m glad we gave them something, but I wished we had given them more.

The next day, the driver of the truck my new friends would all be riding on asked me if I’d like to join them for a while. He said the main road down the DRC’s eastern borders was terrible and there were very, very few vehicles travelling on it. In addition, marauding, unpaid, often drunk soldiers or rebels could be a real problem for a solo traveller on foot, he said. For $10-a-day US and pitching in with the cooking and washing up, I was welcome—a deal I gladly accepted as I looked forward to more unforgettable experiences.

All photos Tom Barrett