Posters, Passports and British Snobs

I had a fascinating, if occasionally scary time in Northern Ireland in 1971, but I was relieved to leave (London) Derry and cross into County Donegal in the Irish Republic. My experiences in Belfast and especially the No Go areas of Free Derry were eye-opening and unforgettable, but I was now entering the part of Ireland I had really looked forward to travelling in. I made sure to find a somewhat disinterested Irish border official to stamp my passport because when I left France and reached Ramsgate in the UK on September 25, 1971, my entry stamp specified I was granted a visa on the condition that I stay no longer than one month in the United Kingdom and I wanted proof that I had left the UK and entered the Irish Republic on October 15 – nine days before my month was up.

I carried on hitchhiking and a little before nightfall got a ride from Joseph Brennan, the Irish Minister of Labour, who was on his way home to his constituency in County Donegal. We had a great conversation and I told him about my experiences in Ireland so far. He asked about my heritage and I told him that most of my ancestors came from Ireland, but I did not know where in Ireland. He dropped me off in Donegal town in front of a pub, shook my hand warmly, saying that I should enter the pub and say that Joe Brennan asked that someone give me a ride to the local hostel. Which they did.

Like most young people I had very little knowledge of my family history, but that has changed dramatically in recent years. I now know that my great grandfather, Charles Cooney, was born in about 1830 in the tiny townland of Ardatowel, a few miles south of Donegal town. He later married Unity McFadden in Altoona, Pennsylvania. She was born in the Donegal district of Cloughaneely, an area in which Irish Gaelic is still the first language.

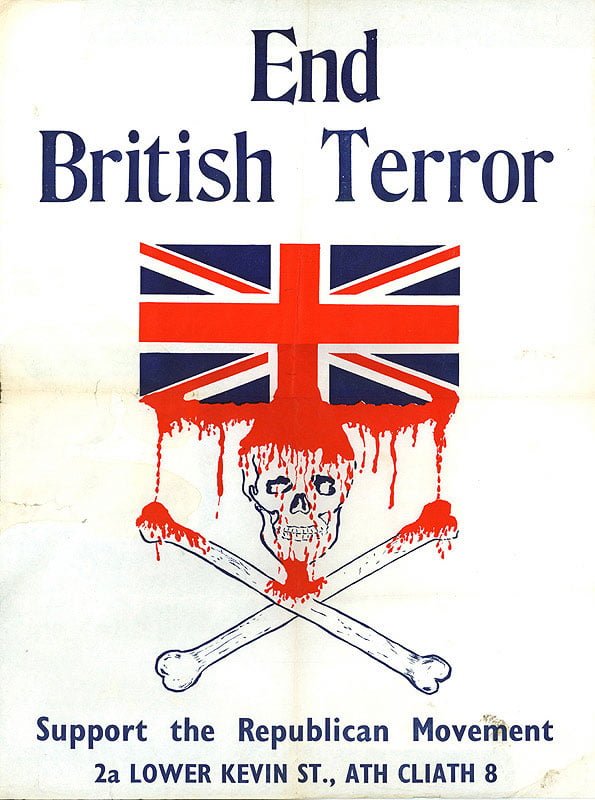

On my way south from Donegal I got dropped off next to what appeared to be a barn beside the road. My attention was drawn towards a Provisional IRA poster on the barn’s outside wall, which proclaimed “End British Terror” and depicted a skull and crossbones with blood dripping from it. I tested the poster to see how tightly stuck to the barn it was and carefully peeled it off the wall, folded it up, and slid it into my backpack as a terrific souvenir of my trip to Ireland. Let me emphasize that I was not, and am not, a supporter of ANY paramilitary organizations, Catholic or Protestant, in Northern Ireland or anywhere else, but that was a helluva poster.

I still remember how friendly and hospitable the people who picked me up hitchhiking in Ireland were. A couple of times, after a good conversation, the driver would say “Do you take a drink then?” A few minutes later I was relaxing in a small-town pub, drinking my pint and enjoying his company. I loved Irish pubs and was often content to order some pub food and a pint, and just listen to the conversations at the nearby tables. No one talks like the Irish and I could never get enough of listening to them. Their voices were like musical instruments and they obviously adored words and seemed to caress them when they spoke. One morning I was trying to thumb a ride when I encountered a chatty older man on the road who talked for a couple of minutes in splendid detail about the changing weather and all the possible outcomes of it, as I listened in awe and delight (add your best Irish accent).

“Well, you know, it’s a fine mornin’ so far, but the clouds are blowin’ in from the west, and it’s a wee bit close, so later there could be the kind of toonder and rain peltin’ down that you wouldn’t put the dog out in, but on the other hand the clouds are moving pretty slow and the sun is about breakin’ through, thank Jaysus, so it may be a fine day after all. Now yesterday it was desperate out and….” Etc.

And then there is this…

One day, while still in the west of Ireland I got picked up by a particularly nice man who asked me questions about how I liked the country and what it was like staying in the hostels. I told him I loved Ireland and I thought the hostels were very nice. I said I’d go out and buy some food after checking in, have something for dinner and talk to the other backpackers about their travels and swapped stories and recommendations with them about places to go and things to see. He asked me if we ever eat steak in the hostels and I replied that I had never seen anyone have one so far. Then he asked if I liked steak and I said yes, definitely, but it’s too rich for my shoestring budget. “Well, then you’ll have steak tonight,” he replied, pulling up beside a store in the town of Gort. The sign read “Sean Duffy, Butcher.” He asked me to wait, entered the store and emerged a few minutes later with 4 pounds of high-quality steak. I thanked him profusely and he dropped me off at the nearest hostel. There were only about four other guys staying there and we each had steak that night. I have no idea whether our benefactor was Sean Duffy, or if he worked at the shop, or was just someone who wanted to treat some of the young people visiting his country, but will never forget his kindness or the generosity and hospitality of the Irish people.

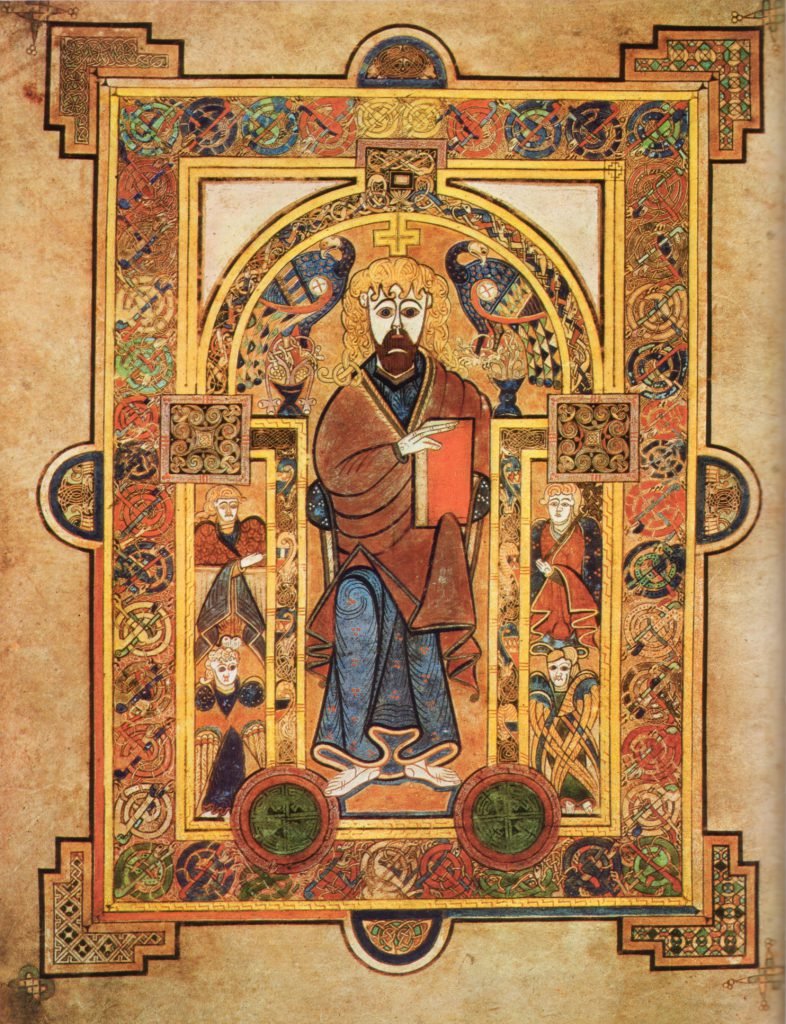

I continued on, having a wonderful time, spending a few lovely days in Galway and then thumbed around the gorgeous Ring of Kerry, as I fell in love with Ireland and its people. There were relatively few backpackers there, which is strange because the Republic was and is safe, friendly and beautiful. I then travelled on across Tipperary, where my grandmother, Mary Mackin, whom I knew well as a young person, was born in the tiny nine-house village of Rehill in 1881. I eventually reached Dublin, where I walked some of the streets which James Joyce described in his famous novel, Ulysses. I saw a play in the famed Abbey Theatre, where the works of W.B. Yeats, John Synge, Sean O’Casey and many other Irish playwrights debuted. I also visited my share of old Dublin pubs and Trinity College, where a page of the magnificent Book of Kells is turned every day.

A few days later I hitchhiked north from Dublin back towards Belfast to spend a night with my pals from Queens University, then thumb a ride to Larne and take the ferry back to Scotland. Luckily, I got picked up by a friendly driver who was headed all the way to Belfast. As we neared the border between the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland he asked me if, by chance, I was carrying anything that might cause a problem with border officials. I said I had a poster that might raise some questions and he asked me to show it to him. He almost drove off the road when he saw the IRA poster. “I’m sorry,” he said nervously, “but there is no way I’m taking you across the border carrying that.” He said if I wanted he would drop me off just before the border post, but unless I threw the poster away he was not driving me across. It was pouring rain and this nice guy was going all the way to Belfast, so I reluctantly gave my poster the toss. A few minutes later we reached the border post, between Dundalk and Newry, which was real bandit country, and realized the building had been blown up a few hours earlier by IRA men, as a border official appeared from the dark in the pounding rain and just waved us through from a fair distance away. What I wouldn’t give to get that poster back. It was an awesome keepsake.

A few days later I hitched through the endless rain across Scotland and England like a drowned rat before finally reaching Dover, looking forward to catching the ferry to Calais. It was November 9th and it was getting damn cold. The time had come for me to hitch across France to sunny Spain.

The British border official perused my passport and menacingly proclaimed that I had overstayed my allowed time in the United Kingdom by 15 days. I took the passport and calmly but firmly pointed out the stamp that showed I had crossed into the Republic of Ireland 25 days ago and told him that I re-entered the United Kingdom south of Belfast three days ago but couldn’t get an entry stamp because the border post was destroyed. In fact I had spent only 24 days in the UK. He insisted in his prissy British way that for the purposes of travel the Republic of Ireland was considered part of the UK and that I had not left it when I entered Ireland.

Now I was pissed off. I said, first, if you look at the writing on my UK entry stamp you will see there is no suggestion that for visa purposes Britain considers Ireland to still be part of the United Kingdom, and no one told me about that policy when I got the visa in Ramsgate. Why should I assume that Britain still considered Ireland a part of the United Kingdom? Shouldn’t you have a policy of telling visitors with a limited time visa that it includes travel to an independent country, the Irish Republic? How was I, or anyone else in the same circumstances, supposed to know about it if your officials say nothing about it, I inquired emphatically. He hesitated for a few seconds and maybe because his arrogance triggered my ancestral Irish temper, or because he was just an insufferable prick, I said that after 700 bloody years of colonization and decades of Irish independence he and his masters apparently still haven’t figured out that Ireland is no longer a British colony. He literally blushed with anger, but did not say a word. What was he going to do? Refuse to let me leave the UK? After a few seconds hesitation, he smugly stamped my passport, handed it over, turned his back to me and I headed for France, thinking that there is no tight-assed snob like a British snob.

Feature image: The Ring of Kerry (photo: InSight Tours Ireland)