Night of the Living Dead

I have travelled a lot in Third World nations and I have had my share of annoying stomach bugs and other minor intestinal ailments, but one time in October, 2008, on the fabled Snowman Trek in Bhutan – a beautiful Himalayan country east of Nepal and south of China – I experienced the worst night of my life. I woke up just before midnight and felt a horrific rumbling in my guts unlike anything I had ever experienced. It just got worse and worse, leading to the inevitable emptying of virtually everything in my digestive system. I will spare you any further details, which you can surely guess or imagine anyway, but let’s just say I weighed a lot less in the morning than I did the night before. When the sun came up I was curled up in a ball, shivering and shaking in the bitter cold at 4,160 metres (13,645 feet) suffering from mild hypothermia and massively dehydrated, presumably from some form of food poisoning. I was also operating on about two hours sleep.

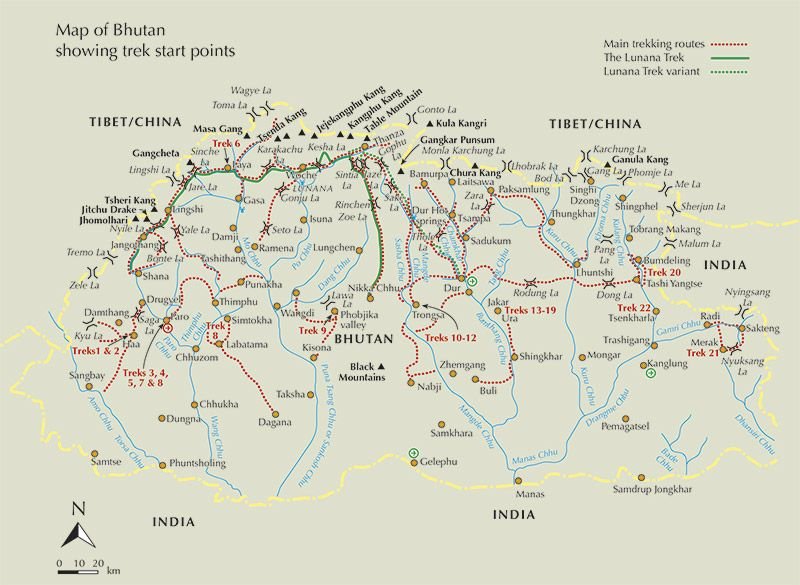

With a great effort I dug through my pack in the middle of the night to find and put on some extra-long underwear, top and bottom, as I had to keep leaving the tent in the piercing cold for obvious reasons. Maybe it was my fault that I was sick, maybe not. Perhaps I didn’t wash my hands as thoroughly as I should have, or possibly something nasty got into my food, although no one else got sick. Or maybe it wasn’t food poisoning at all. Maybe I just pushed my body too hard, racing up to the Jare La mountain pass (pictured above) ahead of everyone else that day, and my body revolted, as some suggested. Or it could be something else entirely. I will never know.

Our American trek leader, Kevin Grange, of Canadian Himalayan Expeditions, said they would have to find a mule for me to ride that day because we had a schedule, the trek could not stop and the logistics were such that there was no practical way I could stay where I was for a day and then catch up somehow. I insisted I could walk it, even though we had a great deal of ground to cover that day, 19 kilometres, and would have to cross our first 5,000-metre pass, but when I couldn’t even pack my bag without help, I realized I had no choice. I felt unspeakably weak, sleep deprived, and somewhat disoriented, but still full of fight. I was going to get there, one way or another. Bring on the mule.

Luckily for me, one of our ten trekkers was an Australian doctor, Hamish McKee, who had become a good friend over the past 12 days. Ironically, I had mentioned to him earlier that I hadn’t thrown up in nearly 40 years. Now he volunteered to walk beside me while I rode the mule and provide whatever medical treatment he could. Hamish and Kevin, who also walked beside me most of the way, really looked after me and I will always be grateful to them. What I didn’t learn until a day later was that I owed a lot to another person, Karma, our head horseman. The other four horsemen understandably declined to spare a mule for a 155-pound trekker to ride on, but Karma agreed to provide one and spread that mule’s load among the others he owned. It was just another example of what a kind and compassionate man he is.

Hamish was carrying a lot of energy replacement packets with him which he mixed in my water bottle regularly to replace the lost minerals, such as sodium and potassium, which the body needs to function properly. I kept emptying my water bottle all day long, taking a deep drink every 15 minutes, and the effect was remarkable. It was like I could feel life and desperately needed energy pouring back into my veins. I now carry lots of those replacement packets when I trek.

My next challenge was riding a mule over very rough and rocky ground with plenty of ups and a few downs. I had never ridden a horse, let alone a mule, so I had a lot to learn. I was told to lean forward when the mule was walking uphill, and backward on the rare occasions when it was going downhill. I found that I needed very strong muscles in my inner thighs to control the animal and mine ached by the end of the day. I guess I should thank the mule, as well, because I was a lot heavier than his typical load, and he made it clear he was not happy, but carried on. For a while. I had to walk the top half of the first long and steep hill because of fears the mule would fall and be injured with me on board. The mules are worth about $900 each, as we learned a few days earlier when we watched in horror as a sick mule tumbled down a huge hill, head over heels to its death with a broken neck. John, one of our trekkers, gave the mule mouth-to-mouth resuscitation in a heroic but unsuccessful attempt to save it. At the end of the trek all 10 of us chipped in to help compensate the mule’s owner.

It was a real struggle but I made it to the top of the hill on foot, stopping a couple of times to rest but always carrying on, with Hamish encouraging me. Every deep gulp of that electrolyte solution felt like a shot of adrenalin, though I was still weak. Later I got about a third of the way up the major climb to the Sinche La (5,005 metres, 16,420 feet) before the mule just plain quit. That was it. He would not be persuaded. He would carry me no further. He had done his job and the rest was up to me.

Slowly but undeniably I was getting stronger as I trudged along. I knew I could do this now if I just took my time and kept putting one foot in front of the other. It was a very tough uphill slog, a zigzag path with a number of false summits, but I finally made it over a rise and saw those beautiful prayer flags that marked the top of the Sinche La. I knew there was almost a 3,000 foot, long, and slow descent to our campsite at Limithang and that I was going to walk every step.

Soon I began encountering people from the Australian-based World Expeditions trekking group, who were in lock step with us nearly every day of the hike and I had come to know many of them. News spread quickly between the groups, so all of them already knew about my plight and many came over to ask how I was doing and offer encouragement. Call it trekker solidarity. I told them I was feeling better all the time but had a long way to go to full recovery. A few minutes later I caught up to the rest of our group finishing up their lunch, and got more encouragement, but didn’t have anything to eat. The mere thought of swallowing solid food still made me nauseous.

I still had three hours of mostly downhill walking to go, but I wasn’t carrying anything, as Hamish walked beside me, packing my stuff along with his. What a great guy and a true friend. The downhill hike was still hard, but I managed it with a few short breaks and stumbled into camp at 4:15 p.m. I joined everyone in the dining tent, continued to drink liquids and consumed a special Bhutanese ginger and garlic soup, which our wonderful cook, Yeshe, made especially for me. It was a great feeling to have covered those 19 kms and even better to know I was done for the day. In the end I rode about 20 to 25% of the way on the mule and I’m not sure if I could have made it without him. I guess I would have had to.

I then staggered off to bed for 12 hours of blissful sleep, only interrupted by the odd call of nature. I finally stumbled out of bed at sunrise to see we were surrounded by beautiful scenery, including the great Tiger Mountain (aka Mount Ganchetta) at 6,840 metres (22,441 feet) looming over us. It was wonderful. Karma came over, smiling broadly, and leading the mule that carried me as far as it could, and I thanked them both with real emotion. I then marched to the food tent, feeling hungry, wolfed down my usual solid breakfast, grabbed my gear and headed out with a spring in my step.

I felt about 85 per cent recovered as we descended 1,200 feet to Laya, the largest village on our trek with 1,000 inhabitants, whose women are famous throughout Bhutan for their beauty, their long, dark hair, and the conical bamboo hats with a spike at the top they wear. The hats are made of darkened bamboo strips woven together, plus colourful beadwork in the back with about 30 strands of white, red, orange and blue beads.

We discovered a store in Laya that had relatively cold beer from Tibet and India, plus some Bhutanese whiskey and one of our trekkers chipped in a flask of scotch as we pretty much drank every drop of alcohol in the general area. 10 days on the trail can do that to you. I’m not sure if it replaced any of my electrolytes, but I enjoyed it. It was like a real party, with everyone participating. That evening we attended a fascinating performance of traditional Bhutanese dancing, which we were eventually invited to join in on, an offer which about five of us, including me, enthusiastically accepted despite our well-meaning incompetence. Then our horsemen, led by Karma, joined in and we all went at it hard, laughing and joking as we tried to follow their lead. I got a bit tired by 10 p.m. and hit the sack, glad to feel nearly 100 per cent.

https://youtu.be/WLYUIbIwyl4

The next day each of us had a turn at the satellite phone and it was wonderful to chat with all three of my sassy kids back home in Edmonton. A little later I heard the loud, long sound of a huge horn and followed it through the village, avoiding some menacing looking Tibetan mastiffs, and discovered a Puja, or Buddhist purification ceremony for a new house. The head monk, who was leading the ceremony, invited me to join him for a cup of traditional butter tea along with the couple whose house we were blessing, and their extended families, and we all sat around together, drinking tea, smiling at each other and trying to communicate. I love the spectacular Bhutanese landscapes, but the many cultural interactions were just as delightful.

That night we went to the local school talent show which was not that different from ones I attended at my kids’ schools back in Edmonton. We also said goodbye to Karma and the other horsemen, as they headed home and a group of yak men came to replace them for the toughest part of the journey, the climb over a 17,000 foot high pass and down into the lovely and totally isolated Lununa Valley, more than a weeks’ walk from the nearest road and a place which very, very few foreigners have ever gotten to. Fewer people have reached the Lunana Valley and completed the Snowman Trek than have summited Mount Everest.

By now I was back in top form and ready to tackle whatever challenges the trek threw at me. Nothing much feels worse than being sick and nearly helpless and nothing much feels better than working through it and appreciating just what a blessing it is to feel healthy again.

Feature image: me, at the Jare La mountain pass (at 4,785 metres/15,695 feet), earlier on the day that I got sick