A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall

The violent thunderstorm erupted without warning. It seemed like one minute our family was walking happily in the sunshine, admiring the lush green meadows and brilliant wildflowers on Malawi’s Mulanje Massif, the highest mountain in central Africa, when suddenly angry black clouds came pouring in, transforming the massif’s bright rolling hills into dark, featureless mounds. “Quick, get out our rain gear,” my wife Philippa shouted, as we pulled off our day packs, slipped rain ponchos over our three children and snapped on our own rain jackets.

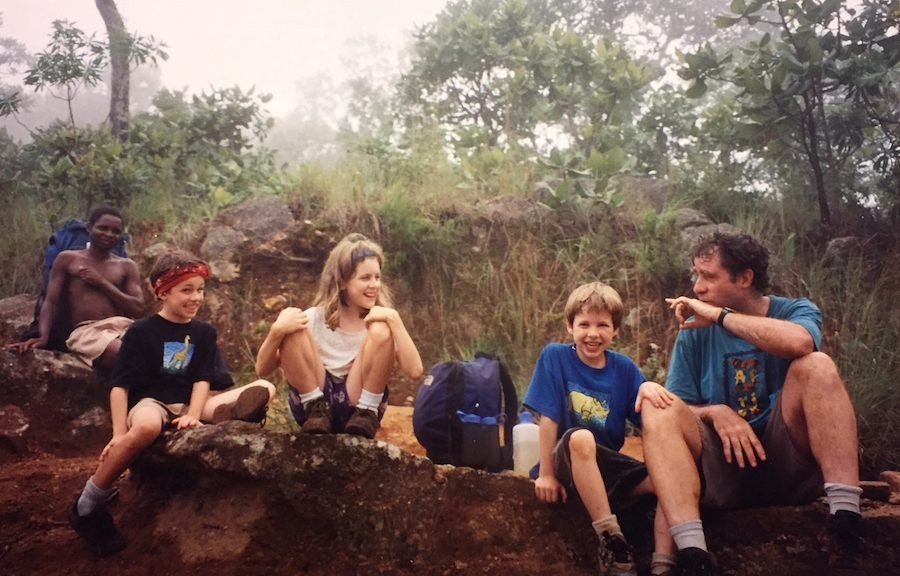

It was week eight of our twelve-week backpacking journey through east and central Africa in 1998. We had left our Edmonton home and brought our children, Rachel, 10, Danny, 8, and Sam 6, to Africa on what we hoped would be our family trip of a lifetime. And it was, even if there were some scary events, like this moment on the Mulanje Massif.

I bent over to tie the laces on Sam’s hiking boots just as the first shattering blast of thunder sounded. When I stood up, Rachel and Danny had vanished into the wall of rain, following two of our heavily-laden porters on the way down to our destination far below. Philippa and I tried to catch up, but it was impossible. Sam just couldn’t move fast enough and his siblings were moving like lightning. We could only hope our young porters, Ronald and Stern, were looking after our two older kids on the steep and slippery 1,000-metre descent over wet sheets of rock and across streams and rivers swollen by the downpour. Hopefully the porters remembered Dorothy, the no-nonsense woman who ran the local forestry office and organized the porters. She pointed a finger at them four days earlier and said sternly, “You take care of those children. Make sure that they are safe crossing the rivers.”

The third porter, Edson, took Sam’s hand and led him expertly over the most treacherous stretches, while Philippa and I slipped and struggled down the muddy trail, each falling a couple of times. I suffered a series of small cuts on my right hand trying to stop one slide over bare rocks. Thank goodness my wife had had an operation to tighten the ligaments in her right shoulder a few years earlier. I vividly recall her lying on the ice in terrible pain at Edmonton’s Hawrelak Park after putting the shoulder out again in a fall. The thought of that happening on the isolated slopes of the Mulanje Massif was chilling. It wasn’t just my imagination running wild, either. Later that day we met a British hiker who fell off the side of the slippery path and dislocated both of her shoulders coming up the mountain.

Philippa and I realized there would be surprises and adventures when we planned this trip with our children across three African countries. In fact we looked forward to it and counted on it. We saved and schemed for two years because we wanted to do something exotic and a bit wild, to take our kids on the kind of rough-and-tumble Third World journeys we enjoyed so much before they were born. We thought it would be a great education for them and an unforgettable family experience, and it was. We also hoped it would be flat-out fun for all of us to escape the daily humdrum and enjoy life on the open road. No appointments or deadlines. Just a lengthy wish list of places to go and things to see, plus some surprising new options which we gladly embraced.

Happily our children loved Africa as much as we did. They were crazy about the animals and the beautiful beaches and seemed to thrive on the constant surprises we experienced. By the time we got around to the Mulanje Massif after eight weeks, they were seasoned backpackers. Fourteen-hour rides on rickety buses? Taxis you have to push to get started? No problem. They would find ways to entertain themselves and loved the company of the local people and fellow backpackers, who treated them wonderfully.

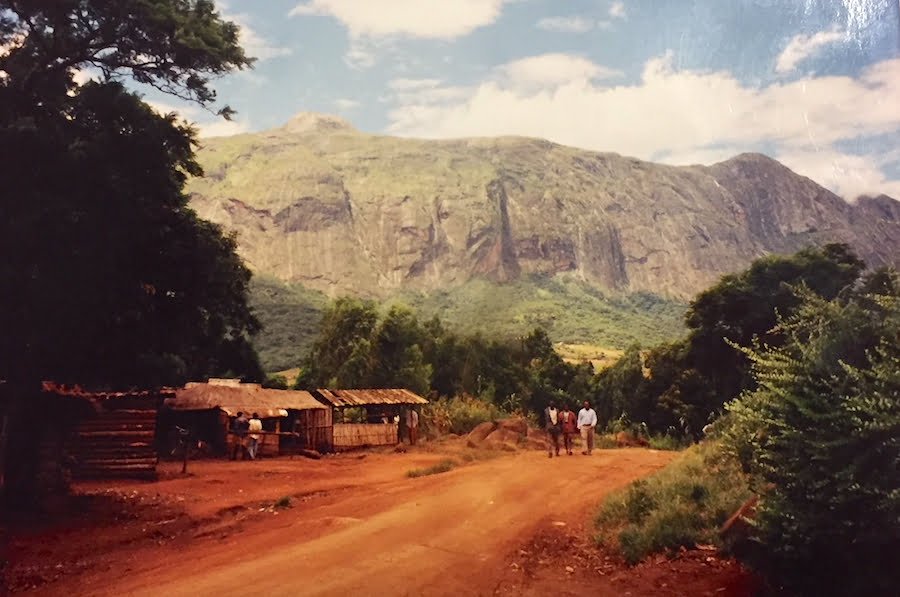

Their eyes widened along with ours when they first glimpsed the massive granite wall of Mulanje towering over the flatlands and tea plantations of southern Malawi. Imagine that someone plucked the famed Ayers Rock (aka Uluru) in the sparsely populated Australian Northern Territory and dropped a much, much larger version of it down in the middle of a fertile African plain. That’s how Mulanje appears from the small villages that surround it. “Are we actually going to climb that?” Danny asked. I had to admit that even from a short distance below it there was no sign of anything but solid rock to walk straight up. But somewhere in Malawi’s great island of stone are very steep dirt paths leading up to a walker’s paradise. The top features an undulating plateau of verdant, rolling grasslands, cut by broad trout-filled streams and punctuated by massive rock outcroppings, forests of cedar and peaks to climb. A wild place that only hikers, a sprinkling of local hunters and wood-cutters visited.

The entire massif covers 650 square kms, including twenty peaks over 2,500 metres high. Throw in seven basic mountain huts connected by clear trails and it’s easy to see why Mulanje is one of Africa’s most attractive hiking and rock-climbing areas. Many people refer to it as The Island in the Sky. It is very inexpensive. Three nights in the huts cost us only $7 US. I can’t remember how much we paid and generously tipped our three wonderful porters, but it was hardly a budget buster.

You can walk between the mountain huts or scramble up the peaks without help, but Phillipa and I decided to hire some local youths to carry most of our gear and keep us on the path. We didn’t quite feel like Stanley searching for Livingstone, but trekking through wild mountain country with native porters gave us a definite taste of old-time Africa, like what I experienced while trekking the circuit hike of the Rwenzori Mountains of Uganda back in 1984. We decided to hire three porters so the kids wouldn’t have to carry anything on the trail and my wife and I could get by with day packs and water bottles.

The grueling, 6-hour long 1,000-metre climb up to the first mountain hut left Philippa and I soaked in sweat and out of breath. I have never walked up a steeper path in my life. The kids looked surprisingly fresh. Like us they were stunned by the sight of barefoot men scurrying down the mountainside, balancing up to three nine-metre-long planks of Mulanje cedar on their heads. For decades, workers on top of the plateau have been cutting the pungent-smelling 12-metre-long cedar trees with hand saws and then lugging the lumber down, an amazing feat of strength and balance, especially considering they have to dodge hikers plodding up the narrow trail. Their wages? A little over $1 per plank.

The plateau at the top of the massif was like a huge wonderland for the kids. They had a blast playing in the stream in front of the Chambe mountain hut and invented a version of hockey on the porch with sticks and pine cones. The kids loved the roaring fire the ancient-looking, toothless watchman started for us, and their appetites were robust. They all slept in a triple bunk bed.

We spent the next day swimming in an ice-cold pool under a waterfall formed by one of the massif’s main rivers. We got back and discovered someone had stolen some of our food. Later Edson and Stern sat with us on the hut porch, reading our copy of the Lonely Planet’s Guide to Malawi and asking about life in Canada. On the third day we hiked for six hours in light rain through lovely countryside that seemed like a cross between a misty Scottish glen and an alpine meadow in Jasper National Park on our way to the CCAP (Church of Central African Presbyterian) mountain hut. Then something happened to remind us we were someplace very exotic and potentially dangerous.

“Snake, snake,” Ronald called out, pointing to the edge of the trail. Everyone froze. “What kind of snake is that?” my wife asked. “Black Mamba” said Stern. Not again! We had already encountered one of the deadliest snakes in Africa on the way down from our three days hiking in the Chimanimani Mountains. Fortunately the snake quickly slithered away, but it was unnerving.

The sound of barking dogs and screaming monkeys broke the silence as we headed on through thick forest. “Hunters,” Edson told us. In a few minutes a trail of bright red blood appeared on the path and continued off and on for a few hundred metres. About an hour later, as we rested in some open grassland, two hunters in ragged clothes appeared out of the mist below. One carried an injured dog on his shoulder; the other clutched a bag containing a dead monkey. A second dog padded along beside them. They stopped for a few minutes, smiling and chatting with the porters in Chichewa, the local language.

That night we had a dormitory to ourselves, sleeping on comfortable cots in the cozy CCAP hut. Our entire family delighted in an old-fashioned hot bath, taking turns stepping into a small vat of steaming water heated up on the fire by the hut caretaker, which also enabled us to dry our clothes. Philippa warmed up some delicious potatoes with salt and garlic, plus spaghetti for dinner.

In the morning we set off under clear skies, unaware of the adventure that awaited. A few hours later we were struggling down the mountain in the pouring rain, fretting over the fate of our children. Troubling questions plagued us. Should we have spoken to them about the importance of staying together if a storm broke out? What if Rachel and Danny got separated from the porters and tried to cross a surging river on their own? Surely they were way too smart to do something like that. Or so we hoped. It was the kind of sudden surprise that is difficult to anticipate, not that that made us feel any better.

I remember the guide book’s suggestion that hikers carry 30 metres of rope on Mulanje for difficult river crossings after heavy rain. I laughed out load at that passage when I first read it. Imagine carrying that much rope in your pack? What a joke. It didn’t seem so funny now, however. I knew there were a handful of rivers and streams to ford on our four-hour journey down the mountain.

Suddenly we turned a corner and encountered some very wet but familiar faces trudging up the trail towards us. It was five people we had met a week earlier at a backpacker’s hostel in Zimbabwe. Dave, a very nice young Canadian man whom our children adopted as a trip legend and nicknamed Sacko, reassured us that all was well. “Don’t worry, your kids are about ten minutes ahead of you and they’re with the porters. They’re fine.” What a relief.

We continued down the path, breathing easier, but still anxious to actually see our two oldest children again. A few minutes later we crossed a rising stream and discovered the kids and porters sheltering under a huge rock overhang, waiting for us. Rachel and Danny later told us how Stern had watched over them like a mother hen. Bless him. All three kids were really excited at seeing Sacko again. Despite their rain ponchos, they were soaked to the skin and very cold, especially Rachel and Sam. Both were shivering and shaking.

Philippa and I hugged them inside our raincoats to try and warm them up and considered placing them in sleeping bags. The porters recommended against stopping however. The rain had eased off, but the sky was still coal black. We couldn’t spend the night there and the longer we waited the harder the rivers and streams below would be to ford, they said, and we accepted.

An hour’s walk on increasingly flatter ground brought us to a knee-deep river that was flowing furiously. The porters hopped from rock to rock lugging our gear across the water then came back and piggy-backed the kids to the other side, although one of them fell down in the river while carrying Sam, but was still able to get him across. Philippa and I stumbling from rock to rock, but made it to the other side. At this point we were all drenched, but the rain had stopped. The hardest part was past and the brisk walking appeared to have re-charged the kids. Everyone was laughing and joking about another crazy day on the trail. I stopped to savour the moment and appreciate how wonderful we all felt. Life would seem so dull when we got home.

A few hours later our family was comfortably settled in a chalet at the foot of the massif. A swarm of young boys was buzzing outside the door, offering to hand-wash our clothes for $1 or run to the village for cold beer and pop if we let them keep the deposit on the bottles. We gladly accepted both offers.

I was uncomfortable about what happened that day, of course, but accepted that the split-up with the kids was difficult to foresee. The lesson? In the mountains, whether it’s Jasper National Park or a remote African peak you can never be too prepared or too careful. The next morning we gave our porters a second round of tips and they deserved it. We prepared to travel to a nearby village to visit Mary, the World Vision foster child of the Kirwins, some close friends of ours, and gave Mary some nice presents from the Kirwins before heading back to our base in Blantyre, Malawi’s largest city, to take a short break before setting out for Lake Malawi and more adventures.

4 thoughts on “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall”

Tom,

I really enjoyed reading about your family’s adventure!

Thanks Mary Jo. We were an adventurous family. There are two more posts to come about our Africa journey, which all of us agree was the best time we ever had as a family. A few years later we did it again, pulling the kids out of school and spending 8 weeks in Nepal and three weeks in Thailand, another great family experience, which I will ultimately write about. Some people question the long periods of missing school, but the kids were all top students and what they learned on those trips has stayed with them. Glad to hear from you.

Tom! It’s Dave (aka Sacko). Very excited to have found this story online. Reach out if you see this, david@davidmauricesmith.com. Would be great to reconnect 🙂

Hey David (Sacko) My kids still remember you! Rachel (the oldest) and Sam (the youngest) both live in Montreal. Danny works at Legal Aid in Toronto. He is getting married in August. Sam has been camping in Guatemala and Mexico for six weeks. I will pass this on to the kids. I retired 14 years ago and have travelled and trekked in Nepal, Northern India and Bhutan. Philippa and I split up about 16 years ago.