The Boys of Belfast’s Ghettos

Just when something you have been looking forward to for a very long time is near, a totally different and very enticing opportunity comes knocking at your door. You can simply ignore it, or attempt to radically change your plans.

About ten days before I was to fly to Shannon Airport in the west of Ireland, in early May, 1981, and begin a bicycling trip around the country, I realized that a major political event in Northern Ireland that I had been following closely was nearing its moment of truth, possibly opening a journalistic door for me.

For almost two months, Provisional IRA prisoner Bobby Sands had been on a hunger strike at the Long Kesh (or Maze) Prison outside Belfast, followed by many of his fellow Catholic paramilitary inmates. They were protesting British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s refusal of their demand to be treated as political prisoners, not ordinary convicts, entitled to wear their own clothes, be housed with their fellow IRA inmates, receive extra visits and parcels, and be exempted from prison labour. The British had granted them that status in 1972 and taken it away in 1976.

These came to be known as the ‘five demands,’ but the Iron Lady was not for turning. Or any form of compromise. Nor was Sands, or the other hunger strikers lined up behind him. The 27 year-old leader of the H Block inmates was the first to refuse food on March 1, and was expected to die soon as his weight dropped to nearly 100 pounds and he had begun to go blind. His death, which would surely lead to Catholic rioting in Belfast and elsewhere, would not be the end of it, of course. Francis Hughes, who stopped eating two weeks after Sands did, was next, and there were many others to follow.

The Northern Ireland IRA hunger strike was rapidly becoming one of the biggest stories in the world and even though I had just 16 months of reporting experience with the Edmonton Journal, I decided to ask my bosses to pay the slight cost to move my flight date forward and change my destination from Shannon to Belfast. If they agreed they would pay my salary and expenses while I covered the hunger strike for them—until Sands’ inevitable death and funeral. Then I would use what time I had left for the bike trip. I didn’t think I had much of a chance as they had already turned down a far more experienced reporter in our newsroom who was born and raised in Ireland, but I had nothing to lose and a great journalistic opportunity to gain. Besides, choosing me would save them a lot of money as I had already paid for round-trip tickets. Fortune favours the bold, and at the worst it would signal that I was ambitious. To my surprise and delight they approved my request.

After I returned from Ireland, I learned that our legendary publisher, the late J Patrick O’Callaghan—who was out of town at the time the decision to send me was made—said he would not have approved it because I did not have enough experience, which was certainly a fair position to take. I just hope he changed his mind after reading my stories.

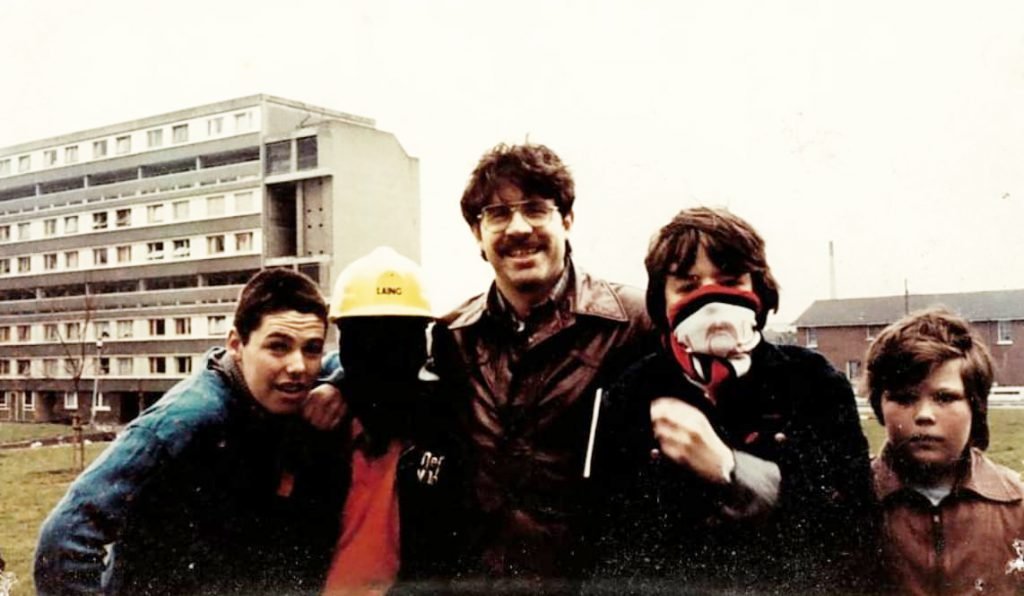

My first story was a feature, focused on the poor youths in the hardcore Catholic and Protestant neighbourhoods of Belfast—the Falls Road, the Shankill Road, Divis Flats and Ballymurphy. With the help of a local social worker, I talked to an 11-year-old who proudly showed off his badly burned hands from throwing petrol bombs at British soldiers. I also interviewed an unemployed, semi-literate, 17-year-old Protestant school dropout who stole to make ends meet. His hard-drinking father hadn’t worked in eight years and his older brother had never worked.

These were the boys of Belfast’s ghettos, born in poverty and raised under the shadow of a gun.

They had lived with violence and hatred for the 12 years of the Troubles, as the locals called the battles between the opposing paramilitary organizations, plus the Provisional IRA vs the British Army. Some of the kids had seen older brothers killed or turned into killers. Many had seen their fathers lose their jobs, their hopes and their self-respect. Most felt more comfortable with a petrol bomb than a soccer ball.

The walls of the Catholic ghetto of Ballymurphy were smeared with political graffiti, including a striking mural painting of Bobby Sands, who narrowly won a by-election as the MP in the riding of Fermanagh and South Tyrone, April 9, 1981, less than four weeks before his death. The almost entirely Protestant Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) had virtually abandoned Ballymurphy, leaving a vacuum filled by the Provisional IRA, apart from occasional visits from the British army. “This is no place for the young,” said social worker Brian McLaughlin. “Most of the kids have never experienced a normal life. There’s no work, no place to play and no future. Out of frustration and sheer boredom, they turn to drinking, vandalism and rioting.” A nun who ran a centre for battered wives said the children desperately needed a place for normal play. “For God’s sake a playground would make a difference,” she told me. After four years of fighting for that playground, she was ready to give up. “I’ve talked and written to everyone who would listen to me, but there’s no hope. No one’s going to build a playground in a place like this,” she said sadly.

What passed for a local playground was really a garbage dump, filled with burned out cars and piles of trash which the local kids played in. “Rioting is fun,” said one boy I talked to there. “We all throw rocks and petrol bombs at the soldiers.” The smallest boy with the dirtiest face offered his opinion. “When Bobby Sands dies,” he said, “there’ll be murder in Ireland.”

Later I spent a few hours in the Catholic neighbourhood of Divis Flats, talking to some young boys about life in their rough West Belfast housing complex. They spoke freely about their various exploits and encounters with British soldiers. I remember asking what they did when trouble came and one hard-faced youth looked me in the eye and said coldly, “You’re trouble.” Before I could reply, trouble arrived. A couple of trucks full of armed soldiers roared up and some British Tommies jumped out with their weapons pointed in our general direction, even though nothing untoward was happening. We all ran like hell to the nearest building to avoid being struck with rubber bullets, and stayed inside until the soldiers left. For me, that was the most frightening experience of my time in Northern Ireland. For those rough and ready kids, it was just another day on the mean streets of Belfast.

My next feature story depicted the plight of some of the most hated men in Northern Ireland, British soldiers. Snipers fired at them, children threw stones at them and people cursed them to their faces. They were welcomed with open arms by the Catholic community when they first arrived in 1969.

Everything changed after a series of nasty incidents, particularly the Bloody Sunday massacre in (London)Derry in 1972 when British paratroopers fired on peaceful, unarmed civil rights demonstrators, killing 14 and wounding another 14.

They were hated by Catholics who widely regarded them as tools of the Unionist or Loyalist majority. “Let’s face it, these people hate our guts,” said Allan, a young British soldier patrolling the Catholic Falls Road, who declined to give his last name for safety reasons. “They’d tear off our legs like spiders if they could. They call themselves Christians. Then they come out of church and stone us,” said the 22-year-old recruit from Manchester.

Allan’s face brightened and he smiled broadly when asked about Belfast’s notorious street urchins. “The kids are great,” he said, laughing. “They give us hell, but they don’t really understand what’s happening. In England the kids play football on the street. Here they search out the army trucks and stone us.” He described the IRA as cowards and related how his best friend was killed by a sniper’s bullet on his 18th birthday, two years earlier. He shook his head slowly, then said “I’m a British soldier. I’m not going to let those bastards get me down.’

I also talked to an older priest in the Divis Flats who told me stories about kneecapping, a practice widely used by the provisional IRA, or Provos, who controlled the streets of the hardcore Catholic ghettos and punished petty criminals, drug dealers and anyone else who offended or disobeyed them. The barrel of a handgun would be placed at the back of the person’s knee and a shot fired into it. Sometimes the shot came directly through the front of the kneecap and sometimes not. About 20 per cent of the approximately 2,500 people who were kneecapped by the Provos during the Troubles ended up with a permanent limp, and a small number had to have a leg amputated up to their lower thigh.

The priest said it was not unusual for people who learned they were on the list for kneecapping to make an appointment to get it over with, hoping they would get more lenient treatment. He said he knew of one case in which the victim phoned for an ambulance just before his kneecapping, so he would receive quick treatment and painkillers afterwards. It wasn’t always just one shot in a knee, sometimes it was both knees or an ankle or elbow. In the most extreme cases it could even be what they called a “six pack,” both knees, both ankles and both elbows. To me, the cruelty and brutality of these actions were almost incomprehensible, but that is what life is like in warring communities torn by hatred. The bitterness of both tribes legitimized—for many—actions they would regard as atrocious in normal circumstances, which no one had experienced in a long time.

In my opinion these portraits of the lives of ordinary people in troubled Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods where most of the paramilitary volunteers grew up and still lived in was more important than the predictable blather from official spokespeople on all sides. As long as these rival communities continue to live in self-segregated ghettos where hatred of The Other is lesson one, nothing much will change. Both tribes were prisoners of their own twisted views of history. Like the Serbs and Croats, Israeli Jews and Palestinians, Hutus and Tutsis, etc.

In the words of James Joyce’s Stephen Daedalus in Ulysses, “History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.” To understand the roots of this conflict you have to know the long and checkered history, but to ever get beyond it, you have to at least try to forget, forgive and realize your enemies aren’t much different than you are. Both sides did terrible things and arguing that one was worse than the other is futile.

The Good Friday Agreement, signed by both the British and Irish governments in 1998, and approved by a majority of the people of Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland in referendums, normalized the status of Northern Ireland. It included the decommissioning of all weapons (theoretically) and dramatically reduced, but did not end, sectarian violence. Ian Paisley’s Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) was the only major one that opposed the agreement. Since then systemic issues like government discrimination against Catholics and rampant gerrymandering have largely been effectively addressed. The remaining question is—what will happen if a vote is held someday on uniting the six counties of the north with the other 26 in the Irish Republic? If Catholics become the majority in the north—which is about 48% Protestant and 45% Catholic, with the difference narrowing—and voters choose union with the Republic, I fear there will be blood.

Now as of Sept 22nd, 2022, Northern Ireland officially has more Catholics than Protestants for the first time thanks to new census results. This historical shift is likely to help drive support for the region to split from Britain and join a United Ireland. The shift comes a century after the Northern Ireland state was established with the aim of maintaining a pro-British protestant “Unionist” majority as a counterweight to the newly independent, predominantly Catholic Irish state to the south.

46 per cent now identify as Catholics with the proportion of Protestants falling to 44 per cent from 48. It does not automatically increase United Ireland support.

Read Part II Take Me to the Worst of It here

Read Part III Aye, there goes Bobby Sands here

One thought on “The Boys of Belfast’s Ghettos”

As an intriguing follow-up to this series of stories, the tale of Northern Ireland continues to weave its way into world history, this time directly impacting the U.K. decision to enact a “Brexit.” Fintan O’Toole’s fascinating piece can be found here: http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2017/09/28/brexits-irish-question/