Confessions of a Late Bloomer

A young child’s transition from the freedom of home life to the stifling regimentation of early school years can be a very traumatic experience – at least that was the way it was for me in the 1950s growing up in a lower middle class neighborhood in West Orange, New Jersey. Many fellow students in my kindergarten and Grade 1 classes settled in well. Others struggled initially but coped. I simply could not conform to school life.

I arrived in kindergarten at the age of 4, the smallest kid in the class, already reading and with a deep love of arithmetic, anticipating that school would be challenging and fun. I was so wrong and so terribly disappointed.

We spent our first two years learning what I already knew, which was excruciatingly boring. I soon tuned out the teachers and the very over-crowded class and quickly became a totally disinterested student who dreaded school and adapted by creating a fantasy world of my own – just staring out the window and daydreaming for hours about being a baseball star or what it must feel like to be happy and well liked in school.

My friends and others who know me well will laugh out loud to hear this, but I was very quiet, withdrawn and painfully shy as a child – the direct opposite of the person I ultimately became. For decades I sensed a loud, opinionated, intellectually curious person locked up inside me, aching to get out.

As I was growing up our Norwegian boarder let me read his National Geographics whenever I liked and I trace my life-long passion for travel, adventure and a fascination with the developing world back to those magazines which I looked through and read almost every day. I also owned a wonderful many-coloured globe that lit up, and I especially loved the deep green mysterious Belgian Congo on the globe, located in the very heart of Africa, where I spent five wild and wonderful weeks many years later. It was my way of imagining a far more exotic and happy life than the deeply troubled one I was living.

About once a week I walked a mile to the public library across the street from the Thomas Edison Museum and scooped up biographies of the American Presidents, read every Hardy Boys mystery and whatever else interested me. It was like I was leading a secret life, home schooling myself.

Apart from my near total lack of interest in school I was not a typical troublemaker. I was exceptionally quiet and never directly misbehaved in any way unless not paying much attention and ignoring classroom work was misbehavior. I would even hide under my desk sometimes when we were all told to bring our completed work assignments up to the teacher which all the other students did. In short, I was alienated and miserable. I stubbornly ignored whatever did not interest me but passionately pursued what did. I am by nature either all in, or barely in at all. I was so lost by Grades 2 and 3 that it would have taken an exceptional mentor to light a fire under me. The teachers understandably assumed I was probably a slow learner. Occasionally I surprised and even shocked them, however.

For example, one day we were given lengthy work sheets on division and multiplication. I finally found something interesting and gave it my total attention. A few minutes later everyone but me was slaving over the work sheets and the teacher raced to my desk and angrily demanded to know why I wasn’t doing the work. I blushed and did not reply, but I handed the sheets to her. She stood like a statue poring over them in disbelief, realizing I had already completed the entire assignment and all my answers were correct, far ahead of all the other students. I will never forget the stunned expression on her face. She mumbled something like “good work” without even looking at me and walked away appearing deeply puzzled.

What she didn’t know was that at home I spent endless hours filling up notebooks with calculations of all kinds, which drove my father crazy. He called them my “damn little numbers.” I still obsessively do similar calculations over sports stats, election numbers, Coronavirus cases and deaths, etc. For example, at Oilers games if Connor McDavid scores multiple points I happily recalculate in my mind the scoring pace he is on and his projected end of season points totals. As the English poet William Wordsworth wrote “The child is father of the man.” Put another way ‘the man he is, grew from the child he was.’

A few years later in 1960 when I was 11 I watched my first foreign film with subtitles on PBS and felt as though I was viewing my own troubling life story. I totally identified with the Antoine Doinel character in French director Francois Truffaut’s brilliant and heart breaking semi- autographical film, The 400 Blows, still my favourite film of the French New Wave.

For Doinel, Truffaut and me, adolescence was a very painful experience, featuring corporal punishment, terrible teachers, a deeply troubled home life and near total alienation. The small boy in the film, Antoine, ran away from his dysfunctional home, was arrested for stealing a typewriter and sent far away to a dreadful juvenile detention center in southern France. The movie is a powerful indictment of French society emphasized by the haunting but enigmatic final freeze frame of the film after Antoine escapes and runs for a long time before stopping cold and staring directly at the camera. Is it a plea for help? An expression of his inner pain or anger? A reflection of his parents rejection of him? I don’t know but I felt like his twin brother. Like Antoine, played beautifully by young Jean-Pierre Leaud, I felt like a human square peg being unsuccessfully hammered into a round hole. Like Antoine I still didn’t or couldn’t fit in.

As with many Catholic schools, Our Lady of Lourdes embraced very strict discipline and the nuns ruthlessly dished out harsh physical punishment with Old Testament fury on supposed ‘bad’ boys. I never saw or heard of a girl being slapped or hit by a nun thank goodness, but I saw many defenceless little boys cruelly thrashed for mostly trivial reasons and I was absolutely terrified of the nuns.

I figured I was safe because I was merely a harmless dreamer, not a significant problem. Then one day the bell tolled for me. In Grade 3 or 4 I wrote a test in my religion class for a nun who then left while we stayed in the room and a lay teacher came in for the next class. About 20 minutes later the nun burst into the classroom, raced to my desk, grabbed a hunk of my hair and used it to yank my head back with brute force as she repeatedly slapped me unbelievably hard across my face, loudly yelling again and again “you will never ever write a religion exam in pencil again,” before stomping out of the classroom, still in a rage. I know the brutality is now gone, but nothing can ever excuse what those nuns did to children. Viciously slapping an innocent child repeatedly for the ‘crime’ of writing a religion exam in pencil is clearly child abuse. For countless minutes I shook helplessly amidst the total silence. I can’t recall how long my face stung with pain and shame as silent tears rolled down my cheeks against my will. I now hated both the school and the nuns and was desperate to escape, somehow, someway.

After my beating there was a period of uncomfortable silence and then the class resumed as if nothing had happened. I was just the latest victim, so no one was too upset or surprised. The brutality was commonplace. I have lived with that barbaric act for more than 60 years and still remember it as vividly as if it happened yesterday. I pleaded with my mother to move me across the street to Eagle Rock Public Elementary School, citing bullies as the problem because I was afraid to tell her about what that nun did to me. That’s how scared I was of them. To my great relief she finally moved me across the street for my Grade 5 year and my sister Joan, who was also struggling, to Grade 6.

The public school was definitely an improvement over Our Lady of Lourdes. At least no kids were slapped around by the teachers. I was quickly identified as a poor student, based on my low grades at Lourdes. Even when I did well I got little or no credit, however. In Grade 5 I was a very surprising finalist in the annual class spelling bee, which clearly puzzled the teacher, Mr. Sorakapud. A bright female classmate and I were the last students still standing out of about 30 pupils. Repeated attempts did not break the deadlock. As an avid reader I was quite a good speller. And now, for once, I was actually having fun at school and really wanted to win something. At that point Mr. Sorakapud told me in front of the class that I should be a gentleman and let the girl have the prize that goes to the winner. I tartly replied that this was a spelling bee not a lesson in etiquette. Why not choose harder words and have a legitimate winner, I suggested. He totally ignored me and just handed her the prize, whatever it was. I spelled every word I was given correctly and STILL lost. Story of my life. Well, of my young life.

Later that year Mr. Sorokapud gave the class a surprise multiple choice current events test after a week of all-day classroom work on that subject, which I thoroughly enjoyed and followed very closely. I got 49 out of 50 multiple choice questions right for a 98, missing only the last question, far ahead of any classmate. Instead of congratulating me Sorakapud pulled me aside after class and suggested I must have cheated somehow. For the first and only time in my entire school life I got really mad and demanded that he tell me how I supposedly cheated. He had no answer. He obviously thought he had me pegged and this piece didn’t fit into his shallow and lazy assessment of me. Sure, I didn’t do very well in class most of the time because I was often totally bored and daydreaming but when I was interested I did very well. What he didn’t know was that I was totally fascinated by current events. I read the Newark Star Ledger closely every day, avidly watched the news on television and was deeply interested in politics, local and world events, even though I had no one to talk to about it.

There were no marauding nuns at Eagle Rock but the teaching standards weren’t much better. My grade 6 teacher, Miss Cowan, was a prime example. We spent at least a third of our classroom time each day learning how to square dance. I am not making this up. Every day we would have to move our desks into the corners of the room so we could square dance for hours. In Grade 6? What kind of school would allow such a thing to go on for years? Why didn’t the parents demand an end to this nonsense? I assume they didn’t because we lived in a generally poor neighborhood with few if any involved and demanding parents.

There was another factor working against my sister Joan and I – our home life. My mother deeply loved her two children and sacrificed greatly so that we could have nice clothes like the other kids. She put our needs far ahead of her own, though I didn’t realize that for a long time. I can’t imagine how we survived our childhood. The problem was my father. He was a very nasty, very bigoted and selfish alcoholic who spent most of his paycheque as a grocery clerk on booze, which didn’t leave much money for the rest of us. He would come home from work every night very drunk and very loud which our unfortunate neighbours had to endure as well.

On a few occasions in her high school days when my sister was on the phone with her Jewish boyfriend my drunk father would yell out anti-Semitic tripe such as “Hitler should have finished the job.” What a disgrace. What an embarrassment. When my mother was at the hospital after giving birth to Joan my father shacked up with a drunken floozy from his favourite bar. He almost totally ignored me but one night he slapped me around very hard when I yelled at him to leave my mother alone.

The only enjoyable thing that happened in Grade 6 was my first IQ test. I loved it. It was the most fun I ever had in elementary school. The test was delightfully challenging and the results came as a total shocker to Miss Cowan and no doubt Mr. Sorakapud. I would give virtually anything to have seen Sorakapud’s reaction to my test result, which I only learned about the next year.

I was still mostly a bored daydreamer who only participated in class if it was something I found interesting or faced a direct question. Miss Cowan was very nice to me, however, after the IQ test and she even told the class one day that I was exceptionally smart. I don’t think they believed her. I’m not even sure I believed her. By that point my self confidence and self esteem were essentially non-existent. All I had was my books, my math, my sports, the news, and my daydreams. I had become a classic underachiever and a lost child suffering from a deep depression. School was my daytime nightmare.

It didn’t get any better. In Grade 7 I went to Thomas Edison Junior High School, a very rough place with numerous bullies and only a few competent teachers. The school had six divisions in Grade 7. The top students were placed in 7-1, the bottom students were placed in 7-6 and the rest were placed in the other four classes which were considered equal. No doubt thanks to my IQ test I was placed in Grade 7-1. Within a month I was rightly moved down to 7-5, however. Nothing really changed.

One day I was called down to the principal’s office. To my surprise he said he had been looking at my grades and my IQ test result and asked if there was anything he could do to help me, adding I was always welcome in his office, which was very nice. Thanks to him a school psychologist was soon brought in to administer a much longer and more extensive, one-on-one IQ test, no doubt to determine if the previous test result was a huge fluke. In fact I recorded the exact same score as the first test, though I didn’t know that yet.

I was always small and thin and had never been in a fight in my life. One day at Edison I was basically forced to fight a much bigger and stronger student. I’ll call him Richie. I was standing facing away from the thug that day when he suddenly hit me incredibly hard on the jaw with a huge, dirty sucker punch from behind. That really hurt but now I was trapped. I couldn’t run away, though I really wanted to. We went to a grassy area near the school and the fight was on with another older student, Billy, acting as the referee to keep it clean. Ritchie knew how to fight and he caught me with a few very hard punches to my cheeks but in an act of desperation I managed to get him in a secure headlock and choked him with all my strength. He could not punch effectively in that position of course and desperately bit me on my side. I kept on choking him even harder in response and he was now gasping for air and moaning like a baby. Billy told him to stop biting me and when he didn’t stop Billy punched him very hard in the kidneys and he gave up, crying pathetically. My jaw and my cheeks were sore for at least a week but I didn’t tell anyone about that. Happily, Richie didn’t ask for a rematch and never bothered me again. This was a rite of passage that almost all boys face, often more than once.

The principal recommended my mother take me to see a psychiatrist to try and find out why I was such a loner, under-achiever, and day dreamer. I came from a poor family and the cost of the psychiatrist was a burden that proved largely useless. It’s quite possible I had some youthful psychological or physical condition such as dyslexia, late puberty, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). I suspect my father’s genes were part of the problem but I just don’t know. I did not make friends easily and was mostly just plain bored in social situations. The psychiatrist told my mother about my IQ test results and she shared them with me.

I took yet another standardized IQ test at Edison in Grade 8 with all the other students and got the exact same result for the third time, although I didn’t know that for another two years. Once again it was a lot of fun. I’d be happy writing those tests every day. It was very challenging and I loved that. Unfortunately, my grades were so low I had to go to summer school to avoid repeating a grade.

After another wasted year my mother decided I should go back into the Catholic system, as if that would help. I had to take another standardized (but not IQ) test, submit my dreadful school grades and list my three Catholic High school preferences. Given my grades my mother believed it appropriate to put two of the less prestigious local Catholic high schools first and second and made the third choice Seton Hall Prep School, the top rated academic Catholic high school in New Jersey, just for the hell of it. I must have really aced that standardized test because I got accepted by all three schools and my ever optimistic if not realistic mom chose Seton Hall, an elite all-boys school in nearby South Orange.

I soon discovered how miserable and toxic the atmosphere of a school could be without the civilizing presence of females. I was regularly tormented by a much older and bigger Grade 10 bully who on one occasion knocked me unconscious with a sucker punch to my stomach for no reason but his own sick pleasure. He laughed when I came to and threatened to do far worse if I reported his actions to school officials and I believed him. I knew my life at Seton Hall would become impossible if I complained about him, so I endured as best I could and avoided him as much as possible. There was no place there for “squealers” or “rats” but plenty of room for bullies apparently. It was like a British private school.

I barely survived Grade 9 and totally crashed and burned the following year. I had one teaching mentor, Fr. Higgins, who was kind and took a genuine interest in me. In Grade 10 he looked up my school records and having a degree in psychology asked if he could give me yet another very lengthy face-to-face IQ test, which he confirmed produced my fourth straight identical score – 140 — which he told the class about for some reason. I continued to get horrible grades and got the boot from Seton Hall, which was fine with me. My only happy memory was seeing Seton Hall’s basketball team come back from ten points down in the fourth quarter to win the New Jersey Catholic state championship in overtime at Atlantic City.

Unfortunately, I had to go to summer school yet again to avoid repeating Grade 10. What a way to ruin summer. That landed me back in the public system for Grades 11 and 12 at West Orange High School.

My years at West Orange High were a step in the right direction for once. To my delight there were much better teachers and students. My grades were still a bit below average but they were definitely an improvement, especially in Latin. I also made some new friends and competed well on the varsity cross country and track teams. I also remember a female science teacher who reached out to me and was as happy as I was when I got a top grade in a science work project. If only there were more teachers like her I might have blossomed a lot sooner.

My grades were okay but not high enough to get into a really good college or university. In the United States there is a college for everyone if you have the money and I ended up at Buena Vista College in Storm Lake, Iowa, my one experience of Midwest America. I was exhilarated by my near total freedom and soon stopped going to some of my classes. Sorry mom. I remember once deciding it was time to start attending a course that I had skipped for two weeks only to discover I couldn’t find the classroom anymore.

On the bright side, I made a good friend from Iowa named Glen who was a nice guy and a very good pool player. He didn’t skip classes but he taught me how to play pool and from then on I took advantage of the school Rec Centre, which allowed students to play for free as long as there were open pool tables. Like when everyone else was in class. December came and I entered the college’s large annual pool tournament for a lark. Somehow I got on a roll and knocked off Glen, another good friend and a long series of others, making it all the way to the semifinals before I was defeated by the defending champion. Not bad for only three months of playing. That was my only achievement at Buena Vista as I flunked out by Christmas. At least my student deferment kept me temporarily out of the draft for the Vietnam War.

I spent the next six months in western Pennsylvania working as a blaster’s helper with my three uncles’ Cooney Brothers Coal Company. My beloved Uncle Chuck took me under his wing. I think those long hard shifts of physical labour were good for me, especially setting off all the explosions which I really enjoyed doing. I would have stayed longer but I realized I was likely to get re-classified by the draft board to 1-A, AKA cannon fodder, and be drafted soon if I didn’t act.

On February 23, 1968, I arrived in Toronto by bus and soon obtained landed immigrant status at the Sarnia border. A few months later my mother received a letter for me from the draft board saying I must report for a pre-induction physical and draft status update. I had no intention of showing up but my Toronto roommate, Bill, was excited about visiting New York City so we hitchhiked to Jersey and I went through the six-hour ordeal of the physical, being poked and prodded, waiting in endless lines wearing only underwear and shoes without socks. On the big day my mother passed me envelopes from two psychiatrists I saw in my younger days and both apparently concluded I was not fit for military service.

At the final stage I handed over the letters and the official opened the first one. He didn’t even bother to open the second one and immediately confirmed I would not have to serve in the army and would be classified as 1Y, only available in times of war or national emergency and the United States never officially declared war on Vietnam. He emphasized that they could always bring me back again and have THEIR psychiatrists examine me, but they never did.

A couple years later the US had a draft lottery and my birthdate just missed getting drawn, not that I would have come back to the US if it had been.

I fell in love with Canada instantly 52 years ago and still have no desire to ever live in or even visit the United States again. It was the best and wisest decision of my life. I had no choice about where I was born, but a real choice about where I would spend the rest of my life.

The US invasion of Vietnam was a war of aggression based on President Lyndon Johnson’s bogus Gulf of Tonkin Resolution as revealed in the Pentagon Papers. The thought of dying horribly in a rice paddy fighting an unwinnable and indefensible war made no sense to me. I still see the invasion as a grotesque war crime by the USA.

My best friend, Peter Kovach, fell for the line that enlisting for three years of choice was better than waiting to get drafted for two years of chance. Peter wrote copious letters to me and my mother describing boot camp and Vietnam. I’ll never forget them. One night in Edmonton I called my mother from a pay phone and was shocked when she told me that Peter had been killed in combat. He suffered third degree burns on 80 per cent of his body in a fire fight and only survived for a few days in a Japanese hospital. I walked the streets of Edmonton all night long thinking of Peter and unsuccessfully fighting back tears. It took me about 15 years to accept his death. I repeatedly dreamt happily of meeting him and discovering that he was still alive and that it was all a mistake – only to remember the dream in the morning or a day or so later. Finally, I stopped having the dream but Peter’s death still haunts me and always will.

I soon discovered that I had to have three years of a modern language to obtain senior matriculation and be accepted at a Canadian university. I learned from Bill that Latin would suffice as a foreign language requirement in Alberta. I moved to Edmonton but I only had two years of Latin, so I didn’t qualify. That decision kept me out of the University of Alberta for almost four years, which turned out to be a blessing.

First, I attended Edmonton’s Eastglen Composite High School where I took a number of required courses and did very well in both English and Social Studies, fairly well in Biology and not so well in Chemistry. Not great, but a significant step up for me. To my amazement I was quite popular for the first time ever. Being both a draft dodger and the only guy in the school who could grow a full moustache, it was cool to know me, a totally new experience. I was even befriended by the toughest kid in school. Best of all I became friends with a group that included a few of Eastglen’s top students whose intellectual heft, creativity and striving for excellence inspired me to follow their example. All of these things helped build my confidence and self respect and I began to read a wide range of challenging books of all kinds. Things were changing.

Since I couldn’t go to the University of Alberta I spent most of the next three years hitchhiking around North America, Europe and West Africa, interacting with fascinating people, reading a great deal, going to rock festivals, crossing the Sahara Desert on the back of local trucks, thumbing through Morocco, Mauritania, Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Togo, Uganda, Benin and Nigeria, spending a night in jail in Texas for the crime of hitchhiking, and generally having a great many crazy adventures, working various jobs, including a year-long one in Prince Edward Island as an untrained social worker.

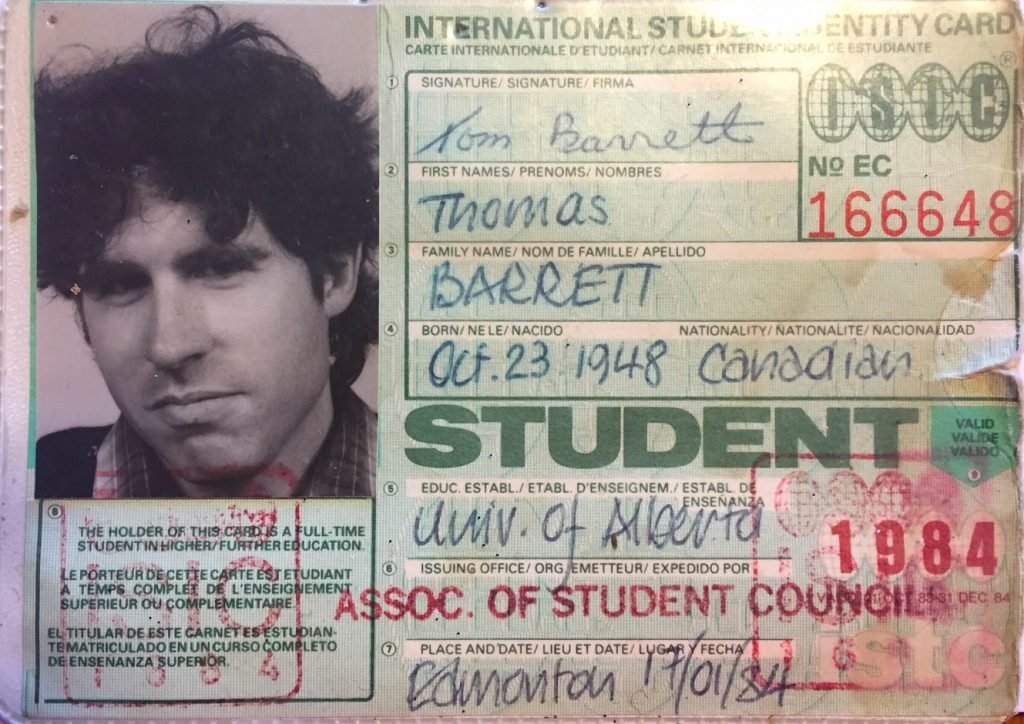

Finally, I was accepted at the U of A as an adult student in 1973. Those four years helped me to mature, grow in confidence and explore the world in preparation for my university courses. I was fresh out of the school of the open road and determined that I could and would succeed this time. I was all in. At last.

First, I got a spring and summer job at Dominion Bottlers, saved as much money as possible and for once I was absolutely ready to do well. I forced myself to develop proper study habits, worked very hard and got good marks (7.9 on the 9 point scale) for the first time in my life. I was nearly broke and landed a job at the new Room At The Top (RATT), the Student Union bar, worked at the university bookstore each summer and lived in subsidized student housing, barely getting by thanks to the meals the female cooks at RATT comped me.

Every year after that I won increasingly greater scholarship money and my grade point average rose to 8.4 in year two and then 8.5 in year three. By then I was already taking some political science graduate student courses from a visiting professor. After a year as a political philosophy graduate student I realized that I was not suited to a life of teaching. I found it extremely difficult to stand before a class to lecture, answer questions, mark papers or control a classroom. It was just too much pressure and responsibility for me. I am not a leader, but I am also not a follower. I am both stubborn and very, very independent minded.

I was quite poor and seriously considered taking the LSAT test and applying for law school, but a friend who was a Journal reporter and the former editor-in-chief of The Gateway when I was the News Editor of the university student paper said The Journal badly needed a copy boy and I got the job the next day. I fit right in immediately. After a few weeks the night editor and later Editor-in-Chief Steve Hume encouraged me to become a reporter and asked if I wanted to write a story. I said yes. Fortunately, the story I was given by assistant city editor Nick Lees gave me a real opportunity to display my journalistic skills. Thanks Nick.

My assignment was to write a feature story about Edmonton’s wheelchair athlete Ron Minor, a star in wheelchair basketball, track and field, and swimming. I interviewed him and immediately focused on his performance in a major international track meet in Europe a month earlier. Just before the race was to begin Minor ran his wheelchair over a board with a nail in it at the edge of the track and it punctured one of his two tires. Unfortunately, there was no time to replace it. Any other athlete would understandably curse his or her bad luck and pull out of the race, but Ron Minor was not a normal competitor. He raced with a flat tire and finished in second place only one tenth of a second short of a gold medal. That heroic race mirrored the way he had responded to adversity throughout his young life. What an inspiration he was.

The next morning when the story appeared the phones in the newsroom started ringing off the hook as an avalanche of Journal readers called to praise the story and salute the inspiring athlete who didn’t know the meaning of quit. I was sitting at the copy chaser’s table and looked up to see The Journal’s legendary publisher, J Patrick O’Callaghan, standing over me and congratulating me on my story. Two days later I heard through the grapevine that I was going to be offered a reporting job and a few days after that I got the job and kept it for 29 happy years.

That Monday I was assigned to sit on the city desk for a week with assistant city editor and future publisher Linda Hughes, to listen and learn. It was January and a late morning story emerged about a plane getting flat tires while landing on the icy cold runway at Edmonton International Airport. Linda told me to chase the story hard and I did, getting some good quotes from an airport spokesman who said flat tires in winter were common. Under intense time pressure I put together a good story even though the airport spokesman tried to take his quotes back. No chance. I finished the story just in time for final edition deadline and it ran at the top of the city page, B1, with my byline. I was still buzzing with adrenaline when my shift ended and I felt that I had found my calling at last. This is what I was meant to do. Forget law school. Forget those vicious nuns. Forget terrible schools and pathetic teachers like Mr. Sorakapud. I was now a very determined and confident journalist with an exciting future in front of him. I was 30 years old, the average age of a classic late bloomer, and nothing was going to hold me down anymore.

A few months later I did my first major investigation. The subject was Edmonton’s Centennial Montessori School. I wrote an expose about some very serious problems in the private school and then learned that eight inspectors from the Ministry of Education had written reports on it. I called all eight on the phone and many of them were sympathetic to my concerns, but all declined to comment or send me his or her own report.

Two days later I showed up for work in the morning and noticed a bulging plain yellow envelope in my mail slot. The only thing inside was a copy of all eight damning reports that I easily turned into a very powerful story which was raised at the Alberta legislature. The lesson I learned was calling all eight inspectors because persistence is always worthwhile and it only takes one to give you the story. It was just like in the movies. And so it began.

I quickly became the go-to guy for out-of-town and out-of-country assignments starting with The Killer Bear of Whiskey Creek, a gigantic and aggressive grizzly who horribly mauled five victims near Banff in 1980.

The following year I convinced the bosses to send me to cover the climax of the IRA hunger strikes in Belfast and the looming death of IRA rebel Bobby Sands. It was the 10 most exciting days of my career. After a few days Sands’ death was announced at 1 a.m. and I quickly found a black taxi driven by an ex-IRA man who took me to a rough Catholic neighbourhood where the locals tossed petrol bombs at the British soldiers who fired rubber bullets and live ammunition back at them. Lots of colour, never a dull moment and a tight deadline to meet. This was what I was made for.

Two days later I walked beside the funeral parade carrying Sands’ coffin in a hearse, guarded by seven IRA men on the way to Belfast’s IRA graveyard. Another seven IRA men stopped the parade and fired a series of volleys over Sands’ coffin, before continuing. I barely beat my deadline by phoning in the story at an all-Catholic taxi station where the drivers shouted advice and criticism of me as I somehow managed to dictate my story with the help of wonderful Journal copy editors. What a great job I had. Editor-in-Chief Steve Hume later told me he attended a conference and used my story as an example of coping with deadline pressure.

In 1984 I was told to hop on a helicopter up to northern Alberta where a small plane had crashed, killing six of the ten people on the aircraft. I learned quickly that NDP leader Grant Notley died in the accident and Housing Minister Larry Shaben was hospitalized with various injuries.

Thanks to lots of luck Byron Christopher of CBC radio and I, with Jackie Northam as our photographer, managed to share an exclusive interview with Shaben in the hospital, scooping everyone else. I just seemed to have a lucky streak going. People told me it was like the news was following me around.

A year later I was sent to Virginia City, Montana, to cover the trial of two unkempt so-called mountain men who looked and sounded as if they just walked off the set of the movie Deliverance. They were on the hunt for a mountain bride to kidnap and share when they encountered and imprisoned world class biathlete Keri Swenson, who was very attractive. A search party rescued Swenson, who was shot accidentally by the young mountain man, but she survived. One volunteer was shot dead by the father who escaped and wasn’t captured for many months.

The next year The Journal made a snap decision to send a reporter to Libya because there were a great many Albertans working in the oil fields there and US President Ronald Reagan was making threatening sounds about bombing Libya. I was their man and a few days later I was sitting a few feet from Muammar Ghaddafi at a press conference and loving the experience and the challenge.

One day I and about a dozen other foreign journalists were flown to the Libyan city of Misrata in the Gulf of Sidra and ended up sailing along the ‘line of death’ with Gaddafi to supposedly challenge the US Sixth Fleet. What a great story. I never had more fun in my life. I also had a few other international bylines along the way.

Shortly before my Libya trip I married a British woman, Philippa, and we had three children, Rachel in 1987, Danny in 1989 and Sam in 1992, changing my life forever.

There were the investigations. In 1987 I wrote two major stories about Montreal mob hit man and convicted murderer Daniel Gingras who controversially got a day pass from Edmonton Institution to West Edmonton Mall, easily overpowered his rather small escort and murdered two more people before he was captured. When a thorough federal investigation was finished I was the first and only reporter in Canada to see and utilize the official report with nothing blacked out. You don’t get that kind of access unless you have earned it by nurturing your contacts and winning their respect.

In 1990 David Staples, Cam Cole and I were finalists in the National Newspaper Awards for stories that established that Edmonton Oilers Hall of Fame goalie Grant Fuhr was a cocaine addict.

Two years later my examination of the use and abuse of psychiatry in the criminal justice system won the Michener Award for public service in journalism – in my opinion the most important of all national journalistic awards. In my spare time while covering the courts over the course of nearly six years I occasionally worked on that package entirely on my own time without consulting any managers, which made some of them VERY upset when I handed in the huge package. I tried to explain that until nearly the end I wasn’t sure if I could make the collection of stories work effectively together, which they ultimately did, obviously.

Managing Editor Michael Cooke, who accompanied me to Montreal for the awards ceremony, told me I should keep the plaque, not The Journal, because I came up with the idea and did all the research and the writing. He also noted that the Journal manager who was supposed to write a covering letter for our entry didn’t bother to do so, shocking some of the Michener judges according to Cooke. I didn’t care at all because I won anyway – totally on my own.

In 1997 I completed the long investigation of a local pedophile priest, Father Patrick O’Neill, ultimately putting him in prison for two years. I couldn’t have done it without the terrific work of a local Catholic, Sheila Williams, who tipped me about O’Neill and provided tremendous help in my investigation. The conversations I had with many of the victims moved me like no other story I ever wrote. There were more investigations of course, such as the inside story of California serial killer Charles Ng, whose extradition hearing was held in Edmonton.

After nearly three decades of deeply loving my job I took a $125,000 buyout and cancelled my Journal subscription because I was very unhappy with what the newspaper had become after it was purchased by Postmedia, an extreme right wing Toronto company, which in turn was owned by an extreme right wing US hedge fund. There were still many good people at The Journal and still are but Postmedia demanded that the newspaper endorse the Conservative Party, federally and provincially, even though Edmonton was a left-wing city which has 19 NDP MLAs and only one right-wing MLA. A great strategy for driving customers away.

Three days after the buyout I started back to my beloved University of Alberta and for a decade took 27 courses for credit, all but two 300 and 400 level classes in English and Film Studies, plus one history course, getting 26 A’s out of 27, including 10 A pluses. My first two classes were Chaucer and Shakespeare and I felt like I was in heaven, loving every bit of it. No two men ever understood human nature better than they did, give or take Plato. I also really enjoyed getting to know some of the best young students.

After that I spent three wonderful months trekking in Bhutan and Nepal in 2008, followed by four months more in Nepal and Northern India in 2014. I couldn’t be happier. My many trips to Africa, South America, Europe and Asia were the fulfillment of my childhood dreams, and I am anxious at 72 to go back and do plenty more if we ever conquer the pandemic.

I hope these stories give hope to parents with children who have struggled in school—children who are bright but underachieving. If they have the drive and the capacity, there is still a good chance they will blossom and find the joy and satisfaction that I have been fortunate enough to experience throughout my many journeys.

11 thoughts on “Confessions of a Late Bloomer”

Tom, there are tears running down my face to recognize a kindred spirit, a fellow autodidact. I skipped Grade 1, and like you I found school less than challenging — and even rather frightening, as I was regularly bullied for being small, unathletic, and the “class brain.” You and I hit the sweet spot A) working at the Journal when we did, and B) having travelled as much as we did, personally and professionally. I eagerly await your next instalment.

Karen, Thank you for your comments. It is interesting that you too had some similar struggles and shared them with me. Yes, we were fortunate to arrive at The Journal when we did. It seems we both are largely self-taught. I thought at one time you were unhappy and I am so glad you and Steve found each other.

This autobiographical account is spellbinding, Tom Barrett. Your description of those brutal early school years had my heart breaking for you. I strongly encourage you to develop this further, into a book, and seek out a publisher. I can even see it becoming a movie.

Thank you so much Deb. I’ve always wanted to tell my life story and how I finally managed to find the right career. I have thought about a book, but I’m not sure at the moment.

That’s a great story. There are parallels with both of us in high school together, some learning disabilities, late blooming and both ending up in Canada after falling in love with the country. My golf obsessed Dad was OK, I thought, but my mother used to say “I’m just thankful that he doesn’t come home drunk every day” which makes me wonder if that was a big problem then and possibly now, still. I wish that I had gotten to know you better back then.

We do have a lot in common apparently, Bob. I also believe that it is too bad we didn’t get to know each other better at WOHS, though I always liked you. Late Bloomers of the world unite.

An incredible journey. As a colleague I witnessed your many triumphs, I had no idea of your struggles. A book could provide hope for a lot of people.

Thanks for your post, Rick. I loved my days at The Journal but in the end I couldn’t wait to get out of there. It was a shame to see a very good newspaper do downhill. There were still some good journalists at the paper but Postmedia has severely damaged the newspaper.

Tom, I remember well your first as a copy chaser, wearing your roommate’s “flood” pants. What great times we had during those Journal golden years. While I was not tortured by nuns, I did experience some of the humiliation and casual brutality inflicted by teachers in post-war Britain.

It’s a fascinating and moving read that has what the old movie moguls demanded …..

a happy ending.

I fell in love with journalism and The Edmonton Journal for nearly 29 years but I wanted out in the end thanks to Postmedia, David. I decided to bear my soul and document my long, strange trip from a very difficult childhood to happiness at the newspaper. This is my 44th blog post and it got more shares and likes than any of the first 33 and some of the comments moved me deeply. Great to hear from you.

What an incredible journey. As a colleague I witnessed your many triumphs, I had no idea of your struggles. A book could inspire others not to give up.