A Stranger in a Strange Land

I was having a great time hitchhiking around Europe in 1971, interacting with locals and other backpackers in Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Oslo and various places in Scotland. Virtually everyone I met was friendly and every place I visited was interesting. One fellow traveller I got to know in Inverness advised me, “If you like Scotland, you’re going to love Ireland.” I hadn’t thought much about Ireland but since almost all my ancestors came from there I thought it would be fun to see the old homeland, so I hitched to Glasgow, had a few great nights at the pubs, and then headed for the ferry. It never occurred to me that my friend might only have been referring to the Republic of Ireland.

I had no idea what to expect when I took the two-hour ferry ride to Larne, in Northern Ireland. I knew that there was serious enmity between Loyalist Protestants, who wanted the North to remain part of Britain, and Nationalist Catholics, who wanted the six counties of the North to become part of the Irish Republic, but I thought it was safe to travel there. My first hint of trouble came on the ferry when I struck up a conversation with a quiet man who told me it was a sad journey for him because his mother had just died in a bombing in Belfast and he was coming over for her funeral. I was deeply shocked and moved and quietly offered my condolences. Then I thought – What am I getting myself into?

I didn’t know that two months earlier the British Government had made the disastrous decision to let the Protestant-dominated Unionist government of Northern Ireland bring in internment, basically imprisonment of anyone suspected of membership in the Provisional IRA. No evidence was required, and for the internees there was no bail, no lawyers, no phone calls, no visitors, no rights of any kind. In short, no justice. The people arrested were thrown in cells for an indefinite time period and many were subject to brutal interrogations. Internment was ostensibly intended to bring order and a drop in violence by jailing all suspected IRA members, but achieved the exact opposite. Violence rose dramatically from the beginning, when British paratroopers burst into unsuspecting Catholic neighborhoods at 4:30 a.m. to arrest suspects. Eleven civilians died that morning in what came to be known as the Ballymurphy Massacre, which predictably spurred violent IRA reprisals. Against the advice of the British, the Northern Ireland government only interned Catholics, even though there was as many terrorist bombings and assassinations from the Loyalist paramilitary groups as from the IRA, a fatal error that exposed the flagrant bias of the Unionist government. Eight weeks later members of the primary Protestant paramilitary organization, the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), bombed McGurk’s Bar, a Catholic pub in Belfast, killing 15 people and injuring 17. Still, no UVF members were interned.

There was rioting in Catholic neighborhoods, mass protests and pitched battles between Loyalists and Nationalist neighbours. Hundreds of vehicles were stolen and torched, factories were burned down, bombs were going off and the hatred on both sides was palpable. That’s what I walked into. Not exactly what I was expecting. I got dropped off in Belfast and was immediately searched, thoroughly and professionally, by British soldiers, who were mostly interested in what was in my backpack. I retreated to a laundromat and washed everything I wasn’t wearing. While my clothes spun round the washers and dryers I struck up a conversation with a friendly young man named Seamus, a student at Belfast’s Queen’s University, who updated me on recent developments, explained internment and invited me to stay with him and his three fellow Catholic roommates, Sean, Patrick and Michael. If not for them I likely would have stuck out my thumb and headed straight for the Irish Republic.

Happily there were lots of normal and entertaining events going on at Queen’s, including a traditional Irish dance, called a cèilidh on that first night. We all drank our share and danced with great enthusiasm, if minimal skill. They were wonderful lads and we had a terrific time. We went to another event the following night on the streets beside Queen’s, and I was feeling a bit peckish, so I joined a queue for a fish and chips wagon. As I waited my turn, Seamus came over and suggested strongly that I drop out of the line. He pointed out that the person lined up in front of me was a uniformed British soldier and a sniper might accidentally shoot me while trying to kill him. Oops. To clarify, Seamus was NOT asking me to move out of the way to let the theoretical sniper do his job, just warning me of the potential danger I was facing. It was sobering. I had never experienced anything like that, of course, but chose to stay in line anyway, mainly because I was very hungry, though I moved as far off to the side of the soldier as I could without losing my place in line.

For the next few days I went for long walks to experience what passed for normal life in Belfast, avoiding the most notorious neighborhoods. It was easy enough to talk to the locals because the moment I opened my mouth they knew I was not a member of either tribe. One day I had a few pints and a good conversation at a Catholic pub. Another time I stopped in a local grocery store in a Protestant neighborhood and a few minutes later heard the muffled, but unmistakable sound of a bomb going off, perhaps a mile away. Everything stopped for a second, but I was the only one who really reacted. People in the shop froze, then acted as if they hadn’t even heard the explosion and quickly resumed chatting and shopping, while I processed uncomfortably what had just occurred. I believe the people who continued living in Belfast during what locals euphemistically called The Troubles, simply accepted, or learned to live with the violence and assumed nothing tragic would likely happen to them.

After eight fascinating, if sometimes scary, days I said goodbye and thanks to my four Belfast pals, who showed me a great time, then hit the road, stuck out my thumb and headed west towards County Donegal in the Republic of Ireland, by way of Londonderry (or Derry), the second biggest city in the six counties of the North. I didn’t plan to stop in Derry, but I got picked up by an American sailor from a nearby US military base who was on his way there. The sailor said he was going to visit his Catholic girlfriend in Derry and added that I was welcome to also stay at her place for a night if I wanted to. I gladly accepted. It would be interesting to see the city, especially if I had a place to stay and someone who could show me around.

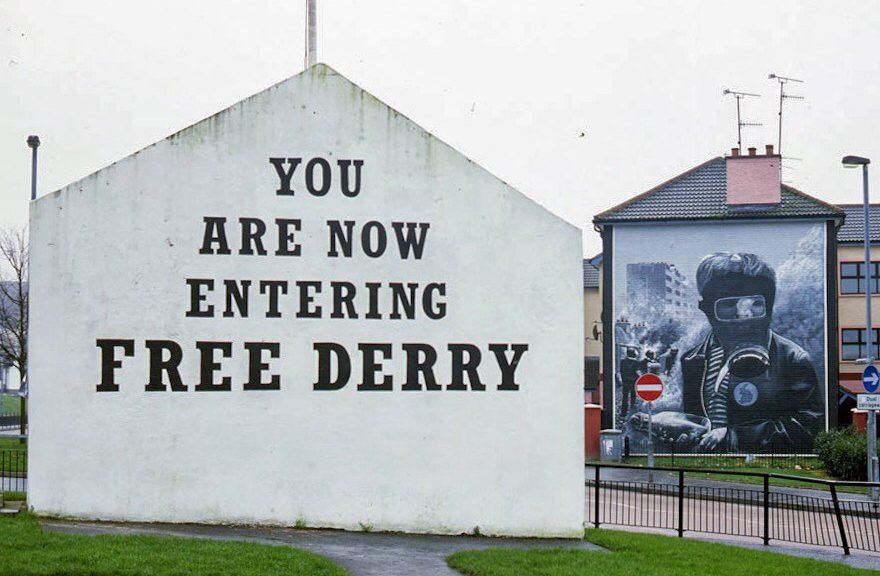

As we drove on the sailor told me we were going to be entering Free Derry. He explained that the term was coined in January, 1969, after a nasty incursion into Catholic neighborhoods by the near totally Protestant Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC). Afterwards barricades were set up in the major Catholic areas of the city and the RUC was not permitted to enter. The British Army took over and the relationship went well for quite a while and the barricades came down. Internment changed everything however. Catholic residents of the Bogside neighbourhood declared their part of the city was now a “No Go” area for the RUC and the British Army. Burned out cars were used to block entrances to the area and armed men manned the barricades to control who was let in.

The American sailor drove right up to one of the barricaded entrances and exchanged greetings with an armed man, whom he obviously knew. He vouched for me and we were allowed in. As he drove down the streets of the Bogside, I gazed at all the defiant graffiti on the walls of many buildings. It was a strange feeling to be allowed into neighbourhoods that neither the RUC nor the British Army could enter. I went for an exploratory walk around the Bogside and I couldn’t help but notice the rough local kids playing pretend war games about killing British soldiers, which was terribly sad. I remembered those children ten years later when as a journalist I wrote about the impossible plight of the tough kids on both sides of the mean streets of Belfast’s sectarian neighborhoods, a story I told in an earlier post, The Boys of Belfast’s Ghettos. It would be fair to say I saw Northern Ireland at its worst in 1971 and 1981.

That night my sailor friend took me for a tour of the Bogside. It was, and no doubt still is, a very poor and rough neighborhood. The thought that struck me deeply was that this was nowhere to live, nowhere to bring up children, but the people of the Bogside had few, if any, alternatives. As I lay in bed that night I thought I heard the sounds of gunshots in the distance. I kept wondering if I was imagining it, and maybe I was, but the sounds continued periodically until I fell asleep. I left Derry the next day and headed into the calmer seas of the Irish Republic, but I will never forget those nine days in Northern Ireland.

Related reading – my return trip to Northern Ireland as a journalist in 1981:

The Boys of Belfast’s Ghettos

Take Me to the Worst of It

Aye, There Goes Bobby Sands

2 thoughts on “A Stranger in a Strange Land”

I went ther , both south and north in 1057 with another RCAF buddie who had relatives inboth areas. Kathryn and I went back about 5 years ago. Must say that both times the south seemed more pleasant. Well don Tom. jc

Thanks JC. Things are pretty quiet in the Irish Republic, but the six counties of Northern Ireland are still pretty shaky.